Whale Shark Profile

The largest fish known to science is a colossal shark with a cavernous mouth; capable of swallowing thousands of prey in a single monstrous gulp! It is truly the stuff of nightmares – but only if you happen to be a small planktonic organism.

A gentle and largely solitary traveller, the whale shark is not a whale, and fittingly alone in the genus Rhincodon, and the only extant member of the family Rhincodontidae.

Whale Shark Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Open ocean, in waters above 21ºc |

| Location: | Warm waters across the world except the Mediterranean Sea |

| Lifespan: | Estimated at 80 to 130 years |

| Size: | Up to 19 metres (62 feet) |

| Weight: | 30 tonnes |

| Color: | Counter shaded; slate grey with intricate white patterning on the top half of the body, solid white on the lower half |

| Diet: | Plankton and small schooling fish |

| Predators: | Healthy adults have no natural predators apart from humans. Juveniles are known to be preyed upon by blue marlin, orca and predatory oceanic sharks |

| Top Speed: | 3 miles per hour, or 4.8 kilometres per hour |

| No. of Species: |

1 |

| Conservation Status: |

Endangered |

Whale sharks are found in open tropical waters above 21ºc and have two distinct subpopulations found in the Atlantic ocean, and the Indo-Pacific.

These benign behemoths spend their lives on the move, migrating thousands of miles in an endless search for food.

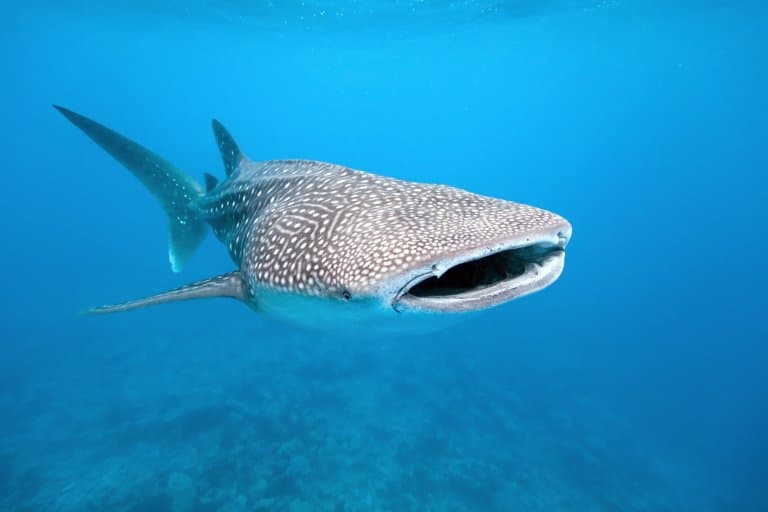

They are filter feeders, which means they swim with their mouth wide open catching plankton, or sucks in volumes of water and with it food.

Their enormous mouths can measure up to 1.5 metres across, and they can filter more than 6,000 litres of water in an hour.

Little is known about the whale shark, or the size of their population. However, the ICUN classifies them as an endangered species due to the frequency of them being caught as by-catches in fishing, vessel strikes by tankers and their late maturity and long lifespan.

Interesting Whale Shark Facts

1. They are the largest shark, and fish

Despite claims of whale sharks measuring over 20m, only one out of every ten whale sharks reaches a length of more than 4m; and the majority of these are under 10m long.

The longest sharks that have been reported are around 12m long. There have been several reliable reports of 18m whale sharks, as well as one dubious estimate of a 20-meter, 34-ton catch from Taiwan in the 1990s.

Regardless, the whale shark is the largest shark in the world and one of the largest sea creatures.

2. They are specialist plankton devourers

Whale sharks are equipped with around three thousand teeth, but these are three millimetres long and not believed to be used for feeding. Instead, they have specialised filtering apparatus inside their mouth which allows them to tackle a wide variety of prey.

Fine filter structures called gill rakers enable them to strain out plankton as small as 1.2mm across, which they gather by ram feeding- simply swimming through plankton-rich water with their mouths agape. 1

3. They might be specialised, but they’re not fussy

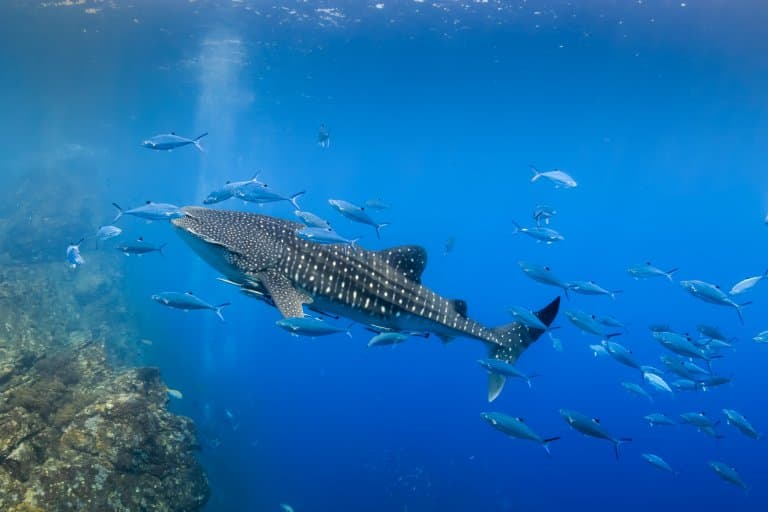

When presented with the opportunity, whale sharks are capable of actively sucking larger food items into their huge mouths and will happily feast on shoaling fish.

They are known to take part in bait-ball feeding frenzies alongside other large predators, and have even been observed vacuuming fish out of commercial nets.

4. They are able to time their migrations with pinpoint accuracy, and we have no idea how they do it

In a few select places, large numbers of whale sharks mysteriously appear at the same time every year, crossing whole oceans to take advantage of brief seasonal feeding opportunities.

Large gatherings are regularly observed at Ningaloo Reef in Australia, where around 400 individuals consistently arrive from hundreds of miles away just as the corals begin spawning. The mechanisms by which they time their arrivals so perfectly over such long voyages are poorly understood. 2

5. Whale sharks are not the only filter-feeding sharks

There are two other extant filter-feeding sharks; the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and the megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios).

Neither is closely related to the whale shark, or even to each other.

The similarities in their size, migratory behaviour, filter-feeding apparatus and even brain morphology are the remarkable result of convergent evolution. The three species do not even share a taxonomic order! 3

6. They have a surprising ancestry

The whale shark belongs to the order Orectolobiformes, also known as the carpet sharks, which include nurse sharks, zebra sharks and wobbegongs. They are not whales!

Whale sharks are totally unique in their order; the other carpet sharks are far smaller and tend to be bottom dwelling species which seldom venture into open water at all. 4

The image above is of a relative and rather oddly named tasselled wobbegong.

7. Where they give birth is a mystery

Whale sharks, like many other sharks, are ovoviviparous- they produce eggs that hatch inside the mother, resulting in live birth.

However, female whale sharks vanish before giving birth to their offspring, and their secret hideaways have not yet been discovered.

It is theorised that pregnant females migrate to extremely remote locations to give birth to reduce the risk of predation to their pups, and have been recorded travelling over 4,800 miles to ensure the safety of their offspring.

8. They vanish for six months of the year

Where whale sharks go between feeding events is unclear. Although GPS tracking technology is slowly unravelling this mystery, we still know very little about their movements.

How they go about the business of finding mates, for example, is completely unknown. Genetic studies have revealed only two major whale shark populations- one spanning the whole of the Atlantic and the other the Indo-pacific, suggesting that they find mates from far-distant corners of the globe.

9. There are specialised teeth on their eyeballs

All sharks are covered in tiny, tooth-like structures known as dermal denticles, which are thought to function as armour and also reduce drag by creating tiny vortices in the water.

Whale sharks have taken this a step further- in addition to a full complement of dermal denticles on their skin, they have evolved specialised denticles covering their eyeballs.

This remarkable adaptation is thought to provide extra physical protection for the eye and to help with retracting it into its socket, as whale sharks are completely bereft of eyelids. 5

10. Whale sharks have fingerprints

Like a human fingerprint, the intricate patterning of spots on their skin is unique to each individual. By taking photos and archiving their sightings, researchers are able to track individual sharks.

11. They are deep divers

While whale sharks spend most of their time at depths of no more than 80 metres, they occasionally perform deep dives to over 950 metres, following the diurnal migration of deep-sea plankton.

Interestingly, GPS tags attached to whale sharks have an unusually high rate of failure, and some researchers think that the crushing pressure they are subjected to on these deep dives might be the cause.

12. They are huge for a reason

Whale sharks are ectothermic- or cold blooded- so when they dive down in pursuit of plankton they face the challenge of the frigid deeper water.

Larger animals lose heat much more slowly than smaller ones, so simply being massive allows the whale shark to forage in the deep for much longer stretches of time.

13. Divers have been known to catch a ride on them

Despite their huge size, and rather scary appearance – they are docile creatures and don’t pose any real threat to humans. In fact, younger whale sharks have been captured playing with divers.

Divers have also been known to hold onto a whale shark and ‘catch a ride’ while studying and photographing these amazing animals.

Whale Shark Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Orectolobiformes |

| Family: | Rhincodontidae |

| Genus: | Rhincodon |

| Species Name: |

Rhincodon Typus |

Related Shark Facts

| Frilled Shark | Goblin Shark |

| Great White Shark | Greenland Shark |

| Hammerhead Shark | Megamouth Shark |

| Tasselled Wobbegong |

Fact Sources & References

- Motta, P., Maslanka, M., Hueter, R., Davis, R., de la Parra, R., Mulvany, S., Habegger, M., Strother, J., Mara, K., Gardiner, J., Tyminski, J. and Zeigler, L., 2022. Feeding anatomy, filter-feeding rate, and diet of whale sharks Rhincodon typus during surface ram filter feeding off the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

- Taylor, J. (1996). Seasonal occurrence, distribution and movements of the whale shark, Rhincodon typus, at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research, 47(4), p.637. doi:10.1071/mf9960637.

- Yopak KE, Frank LR. Brain size and brain organization of the whale shark, Rhincodon typus, using magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Behav Evol. 2009;74(2):121-42. doi: 10.1159/000235962. Epub 2009 Sep 3. PMID: 19729899.

- Compagno, L.J.V. and Food And Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations (2001). Sharks of the world : an annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Rome: Fao, Cop.

- Tomita, T., Murakumo, K., Komoto, S., Dove, A., Kino, M., Miyamoto, K. and Toda, M., 2020. Armored eyes of the whale shark. PLOS ONE, 15(6), p.e0235342.