Water is traditionally quite popular among life forms, and deserts are rather notorious for containing very little of it. So, you might think that turning over a rock in the middle of the Sahara would result in about as much animal activity as doing the same thing on Mars.

But you could be surprised.

There are so many options when designing a desert animal. Adaptations can be morphological, like long eyelashes or wide feet; they can be physiological, like the vascular systems in large, radiating ears; or they can be behavioural, like simply sitting in the shade during the hottest part of the day.

Desert animals have evolved to use a mix of all of these things to allow them to thrive in places where we would just go pink and die.

At least on Earth, even in the most arid, seemingly inhospitable environments, life, uh, finds a way. Animals of every phylum have figured out a way to exist, and even thrive in the desert, and we’re here to champion some of them (in no particular order) and touch on how they do it.

This is a sister-list to the never-released Ten Incredibly Adapted Dessert Animals by “Charlie D. and the Glutton Club”, but one that strives to avoid any gastronomic comparisons and focus purely on the animal itself and how well it’s adapted to one of the most inhospitable biomes on Earth.

10. Sidewinder

It’s great to start with such an iconic animal, known to cowboys for their dangerous bite and boot leather, and known to the rest of us from cowboy movies.

The sidewinder is a relatively small, horned rattlesnake from the Mojave and Nevada desert regions, and while this is not a unique combination, the sidewinder has something that other rattlesnakes don’t.

This little rattlesnake can move in a very special way, coordinating its body so that very little of the snake is in contact with the sand at a time, but perhaps more importantly, there is always a part of the body in static contact with the ground, rather than sliding along it.

This basically means the scales are displacing very little of the loose substrate, and the resulting gait is more of a sideways one, giving it the name.

Sidewinding is great for moving across sand efficiently, and the scales of the sidewinder are specially formed with dimples and holes to further reduce friction.

Interestingly, another type of viper from the Namib desert has solved the same problem in the same way, but aside from these two snakes, nobody else in the order uses it quite as often or as well.

The horns on said horned viper is likely another desert adaptation, functioning as a handy sun visor or perhaps reducing the potential for sand-in-eye situations that no doubt come from living in the desert, especially as the snake likes to bury itself in the sand in ambush. 1

9. Golden Wheel Spider

In the Namid desert, along with the other sidewinding viper, you might be lucky enough to see a cartwheeling spider.

The golden wheel spider is native to this realm and thrives in the steep, sandy dunes in Southern Africa. These are active hunters, which brings them out and about quite regularly, right into the path of the spider’s mortal enemy: the wasp.

Wasps and spiders hate one another. Wasps are known to be very stabby towards spiders, and spiders have generally lost a lot of respect for them as a result.

This relationship is summed up very well in the Namib, where the cartwheeling spider has evolved a somewhat mocking dance manoeuvre to avoid having to make eye contact with the wasp.

The spider is only about 2cm long, and when not in its burrow, uses great sensory organs to actively stalk its prey across the dunes. Unfortunately, this is also where the parasitic Pompilid wasps come out looking for spiders to turn into living egg chambers.

To avoid getting paralysed and eaten alive from the inside out, the spiders have developed a way of moving when startled, which incidentally is also a great way to get out of a conversation you aren’t interested in at a party.

They tuck in their legs and just roll away at 20 rotations and around a meter of distance per second.

8. Thorny Devil

In a totally different desert, all the way over in Australia, a very different animal has a very different adaptation to survive.

The thorny devil is essentially a walking straw. Its scales are ridged into channels that divert moisture via capillary action from most parts of its body to the mouth.

This mechanism is the same way water can be drawn up into the body of plants without a pump, or the way kitchen paper pulls water from the corner of a sheet towards the centre.

While there’s almost no rain in the desert by definition, there is moisture in the form of night-time dew, and so being able to sit there and harvest it without wasting any energy is a very clever little adaptation.

If the dew on its body isn’t enough, it’ll rub itself on the substrate to absorb some more. 2

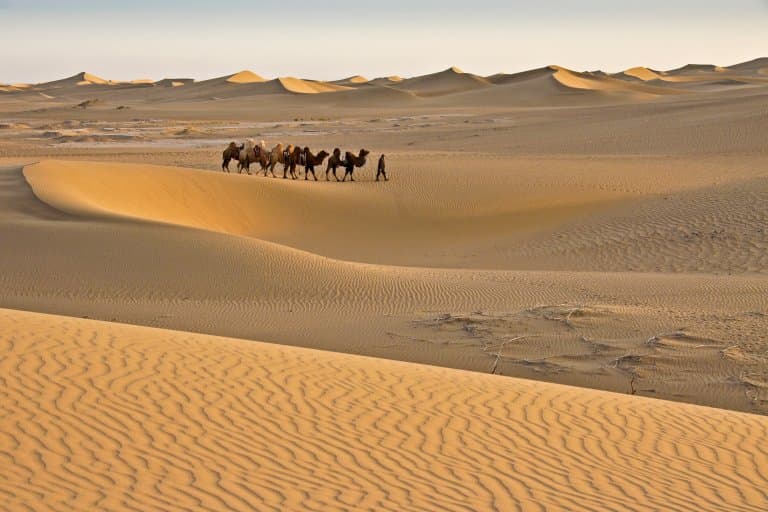

7. Bactrian Camel

Big Camel has lobbied hard to make sure that every list about desert survival contains at least one example from the family, so here’s ours.

Back in the ‘90s, lots of kids were told that camel humps contain water for getting through the desert without needing to drink. This turned out to be false, and the humps are in fact fat storage, which is also really useful when living in an area with low resources.

But camels do also store water, in their blood. The camel’s red blood cells can swell up to over twice their size, providing excellent carrying capacity for water and reducing the need to stay close to a source.

Aside from these adaptations, these camels also have long eyelashes for keeping sand out, hairy ears for the same, nostrils that close like a seal’s (again, sand), and snowshoe-like feet for spreading their enormous watery mass across the loose substrate.

They’re also tough enough to eat desert plants and have twice as many humps as their dromedary counterparts. Bactrian camels are the only wild camels left, though the majority are domesticated.

6. Spider-tailed Viper

Rocketing over to the Middle East now, and in Iran, there’s an animal that would be right at home in an Ancient Greek legend: half snake, half spider, and all viper.

Around the Iran/Iraq border, this highly venomous snake sits in dry rocks, conserving energy by reducing its movement to just a flick of the tail.

However, this tail has evolved into a remarkable lure, which so closely resembles a spider that migrating birds a fooled and approach dangerously close to the snake’s head.

At this point, the outcome is obvious, but the adaptation is considered the most elaborate lure of all snakes and allows the reptile to feed with very little energy output.

For moisture, it hides in craggy, rocky outcrops, where there’s more dew available, but this habitat is reducing steadily, and the species range is getting smaller as a result.

5. Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl

With all these small reptiles and arthropods running around looking healthy in the desert, there’s plenty of food for small raptors to thrive on, too.

From Southern Arizona all the way down into Brazil, the best way to spot such a raptor is to follow the cacophony of angry little birds who are attacking it. This is not a popular animal in the community on account of its penchant for eating their babies, so it’s routinely mobbed by the smaller members and forced to hide inside cactuses.

An adaptation in the owl to this mobbing behaviour is a set of eye spots on its back, thought to be a way of distracting attackers and leading them away from its face.

Yet, this owl doesn’t just punch down, it’s a powerful bird, thought to be capable of taking on animals twice its size. Desert populations have also adapted well to the poor conditions, making very basic nests and generally roughing it like survivalists at the edge of desert and scrubland.

4. Jerboa

Kangaroos evolved to thrive in the heat by hopping along in what is a surprisingly efficient form of locomotion. But they’re not the only animals to have figured this out. Jerboas are far smaller animals but use a very similar strategy to get along.

Their long hind legs are excellent springs, transferring energy well, and providing excellent agility which both reduces energy requirements and allows for rapid escapes from predators, which they can achieve at up to 24 km/h (15 mph).

This strategy isn’t as efficient as many of the animals who use a similar gait but is more specialised for getting out of trouble than long-distance transit.

Behaviourally, they’re adapted to a nocturnal environment, further avoiding predations and the heat of the deserts of North Africa. They also burrow in the sand to further get away from the daytime heat, reducing water loss even more. 3

3. Fennec Fox

The largest mammalian predators in extreme environments are usually no bigger than a fox, and in the Sahara, the Fennec is not far from the top of the food chain. This small canid has enormous ears and is well adapted to the sandy dunes of the African desert.

These ears act as radiators, flushing with hot blood and releasing the thermal energy into the air to help cope with the heat. They’re also nocturnal, so the ears come in very handy when looking for food.

Hair on their feet helps them protect their pads from the scorching sand and keeps them warm on frigid nights.

Fennecs are also generalist omnivores, which is a huge perk in a world where food is scarce. While they love a good insect or rodent, they’ll also eat cactus fruits and other vegetation with high water content, allowing them to survive without needing to drink at all.

2. Roadrunner

Birds are experts in conserving water. Along with mammals, they’re the only animals capable of concentrating urine, and this helps them reduce the water they need, thus reducing their weight and making flight a heck of a lot easier.

Roadrunners don’t fly much, but they do live in arid conditions, so this adaptation is particularly useful.

And like sea birds, they can secrete salt through their faces, which reduces the need to expel water even further by avoiding the kidneys altogether.

Many animals have a bare patch for heat exchange. Humans have it on their faces and the palms of their hands, and some of us have a disappointingly expanding patch on the tops of our heads. Roadrunners have a patch under the chin and this can be wafted by feathers to remove heat and keep the animal cool.

This process is known as gulular fluttering, which is rather sweet, and is a combination of behavioural and physiological adaptations to the hot environments.

Living in rattlesnake territory, roadrunners use the very wits that allow them to escape Wiley Coyote to hunt the snakes in pairs. One distracts the poor beast while the other moves in for the kill. This is very velociraptor of them, and certainly a stark reminder of where they came from.

These birds can go an entire lifetime without drinking water (technically, so can everything else, but at least in roadrunners that lifetime isn’t reduced by it), and get their moisture entirely from their diets. 4

1. Humans

It’s nice to be able to say something good about the human species once in a while, and if there’s anything humans are exceptionally good at, it’s adapting to extreme environments.

Mammals are typically pretty good at homeothermy, and humans are a good example of this. A wide range of internal body temperature for human beings is between 36.1°C and 37.2°C.

This means that whether you’re shivering in a snowbank after falling off your board or lobstering on a beach in Cyprus with a pint, the blood passing through your heart remains within a degree of 37°C, and likely far less.

This alone is an astonishing feat of physiology and one that we commonly take for granted. Humans aren’t the only primates with sweat glands but they do have more than any other, and this is how our ancestors migrated from the forests to the savannas and beyond.

It’s also why we’re relatively hairless compared with other animals, and why we need to drink so much more water (rainforest apes generally don’t drink water more than once in a few weeks).

That bald face we mentioned before acts as a cranial radiator, filled with tiny blood vessels that keep our bulbous brains cool and is unique to humans.

But humans have other adaptations that help the species excel in extreme environments. A developed vocal language has created intricate social structures that now span the entire globe, and the ability to eat more or less anything lets populations of us survive purely on fish and seal meat, while others get everything they need from beans and grains and the occasional insect.

Human hips and the foramen magnum (the hole in your skull where your neck sticks in) have migrated in position to allow for bipedalism or upright walking, and this is also an adaptation to desert survival.

Human locomotion is one of the most efficient ways to cover long distances, and this absolutely gave the species an advantage when wandering across the African continent. This efficiency would go a long way to offset some of the effects of having very leaky skin and presenting less surface area to direct sun at the hottest parts of the day. Incidentally, it also makes us look a lot bigger than we are, which helps when chasing away lions.

Then, of course, humans are more than capable of digging holes, inventing air conditioning, and exploiting the desperation of impoverished communities to cheaply import all the food and water they need so they don’t have to leave the desert at all. 5

Final Thoughts

That completes our list of some of the most well adapted desert animals on the planet.

Despite being one of the most inhospitable habitats, deserts are home to hundreds of different animals. Animals that have adapted to live in the desert are collectively known as ‘xerocoles’.

The main challenges xerocoles face are lack of water, excessive heat and food scarcity.

Species that live in the desert have found unique ways of surviving and have special adaptations to help them thrive in the harsh, arid desert biome.

Fact Sources & References

- Chris Deziel (2018), “Sidewinder Snake Adaptations“, Sciencing.

- Philipp Comanns et al (2017), “Adsorption and movement of water by skin of the Australian thorny devil (Agamidae: Moloch horridus)“, R Soc Open Sci.

- “The long-eared jerboa stands—and hops—in a class of its own“, WWF.

- “Greater Roadrunner“, All About Birds.

- Dennis O’Neil (2012), “Adapting to Climate Extremes“, Journal of Biological Chemistry.