Zooplankton Profile

If you’re anything like the rest of us, you’ll go through most of your life not knowing that there’s no such fish as a sardine. While this is something the Portuguese might argue furiously over, it’s a biological fact. Sardine is a name for any number of oily fish species known to be a bulk food supply for various animals.

Likewise, plankton is not a single thing. In fact, it’s thousands of different things, of varying sizes, and even of different kingdoms. Some plankton are photosynthetic, others have claws. There are even aeroplankton, comprising pollen and seeds small enough to take to the sky.

For the purposes of this piece, we’re looking at oceanic Zooplankton: tiny, floaty animals in the sea.

Zooplankton Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Seas and oceans |

| Location: | Worldwide |

| Lifespan: | Varied |

| Size: | From microscopic to some large cnidarians, up to 2m (6.5 ft) |

| Weight: | Up to 100kg (220 lb), possibly more |

| Colour: | Varied, often opaque |

| Diet: | Other plankton |

| Predators: | Everything |

| Top Speed: | Reliant on currents/wind |

| No. of Species: | 7,000+ described, tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands left to discover |

| Conservation Status: | Not Listed |

We’re going to talk mostly about oceanic animal plankton, but while this is an enormously diverse group of organisms, it’s just a fraction of what’s out there.

Plankton exist in all rivers and lakes too, and serve the ecosystems similarly, as the fundamental nutrient recyclers and food supply.

In the oceans, they support the largest animals on Earth and everything in between. They make up more than 7,000 known species across more than 15 phyla (not to mention the majority of undiscovered species), which makes generalising a little difficult!

Interesting Zooplankton Facts

1. They’re poor swimmers

The first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word plankton is likely an image of something tiny. Most zooplankton are tiny, but the definition relates more to how much control an animal has over its direction.

By definition, plankton are more or less entirely at the mercy of the wind and currents and can either not swim at all, or just about make it around their very local area.

This changes things quite a bit and means that, while the majority of plankton are just animals that are too small to swim against the ocean’s whims, there is technically no upper bound for how large they can get.

2. There’s ‘megaplankton’

Plankton is divided by size, nonetheless, as it makes things useful when considering them in terms of trophic webs and food chains.

Femtoplankton is the smallest category, but this is so small there are no animals this size. Femtoplankton typically contains viruses and the consciences of Nestle execs, things that are below 0.2 microns across.

The next tier, picoplankton, is where we begin to see things that loosely resemble animals: protists float about here, reaching up to about 2 microns across.

Nanoplankton is between 2 and 20 microns, and even here you’d be hard-pressed to find true animals. Here is where you start to find photosynthetic organisms like algae.

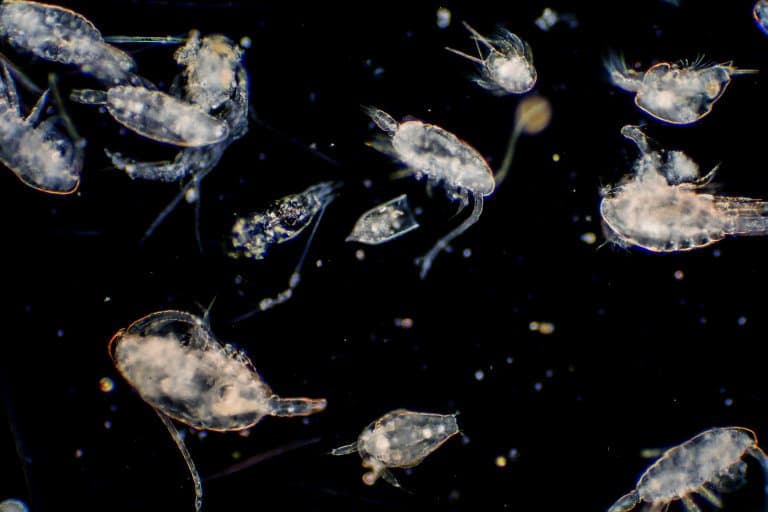

The smallest zooplankton is typically found at the microplankton level. These would be crustacean larvae, rotifers, and other things very few people have ever seen. These range in size from about 20 to 200 microns. When photosynthetic plankton take carbon out of the air, it’s these microplankton that are responsible for eating most of it. This tier consumes up to 75% of the ocean’s primary production.

Mesoplankton are the ones you can just about see with the naked eye, at 0.2 to 20 mm across, and these will include a lot more larvae of various animals like jellyfish, molluscs and crustaceans.

Macroplankton are bigger and can be up to 20cm across, often comprised of shrimp-like copepods and small jellyfish.

Finally, megaplankton make up everything bigger than that and can include some pretty heavy animals like large jellyfish, as long as they stick to the no-swimming rule. Until recently, it was thought giant ocean Molas were the largest planktonic animal at 3 tons, but it turned out they were swimming while nobody was looking, so they’ve now been banned. 1

3. They’re diverse!

Particularly at the smallest sizes, plankton is made up of countless different species, all moving and eating in different ways.

Within planktonic groups, you’ll have filter feeders, predators, scavengers, cannibals, symbiotic relationships with bacteria, and more or less every ecological relationship that’s been identified.

Zooplankton tends to follow around phytoplankton, the algae that take sunlight and use it to capture carbon from the air. These are the primary food for the smallest of animals, who make up one trophic level above the very base of the food pyramid.

This keeps the majority of them near the well-lit ocean surface, but hundreds of species have been found in the deepest parts of the ocean too. 2

4. They’re incredibly useful

Plankton, being mostly comprised of the smallest animals in the world, make up the foundation for the entire Earth’s food webs.

By one rough estimate, 10,000 kilos of phytoplankton are needed to feed 1,000 kilos of small zooplankton, which in turn support 100 kilos of larger zooplankton, which supports 10 kilos of small fish species. This remarkable scale shows why vast quantities of plankton are so critical to the larger ocean animals.

This alone makes them significant, but they’re also really handy as indicator species. As they slip through our nets, industrial fishing doesn’t decimate them the way it does everything else, so they can be used as a test of the health of the marine environment.

Plankton even make up a lot of the ground we live on as terrestrial animals. Limestones, of which chalk is one, are made of layers of deceased planktonic animal shells, laid over millennia and compressed into a solid ground.

Rocks like this form much of the substrate in Europe, and were used to build the pyramids in Ancient Egypt.

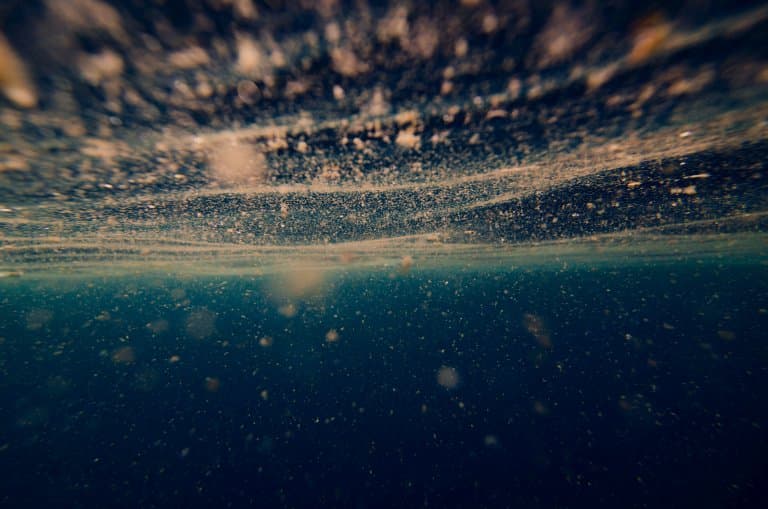

But perhaps most significantly, plankton recycle carbon and other nutrients and power what’s known as the biological pump, which is the ocean’s biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments such as these limestones.

5. But they can also spread diseases

Cholera epidemics have punctuated human happiness with bouts of explosive diarrhoea for thousands of years. But the wriggly little germ is hard to find during the times between such outbreaks.

Illnesses like these don’t just emerge seasonally, they need to be contracted, which means they need to exist somewhere, all of the time, and the challenge with cholera was finding out where it’s hiding when it’s not in our butts.

One hypothesis is that planktonic communities can be reservoirs for bacteria like this, seasonally releasing copious amounts of the germ that correspond with outbreaks.

Planktonic crustaceans have been implicated in this crime by letting the cholera bacteria latch onto their shells during dormant periods. 3

6. The colder they are, the bigger they get

It’s long been known that body size is related to environmental shifts in temperature, because of the role temperature plays in almost every physiological process.

Plankton is generally made up of cold-blooded animals, so is totally at the mercy of the environment in this regard. In cold areas, this means they grow more slowly, reaching maturity at a delayed rate when compared with warmer water equivalents.

But strangely, they also grow much larger, and this is something that’s quite common in ectothermic, or cold-blooded animals. But nobody knows why. 4

7. They migrate

While plankton are defined by their weak breaststroke, they can move around in other ways. Buoyancy can be adjusted without swimming, to allow organisms to descend and rise through the water column as needed.

Some of the greatest migrations on Earth happen daily, and involve billions of little animals sinking or floating up and down in the ocean.

Generally, zooplankton will avoid the majority of predators by hiding in the depths during the day, rising only at night to feed on the stragglers among the phytoplankton who have just come off shift in the photic zone.

These migrations can cover 1,000 meters and carry vast amounts of biomass, rivalling the largest migrations on land. 5

Zooplankton Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | 15 + Phyla |

Fact Sources & References

- Susanne Menden-Deuer (2021), “Promoting Instrument Development for New Research Avenues in Ocean Science: Opening the Black Box of Grazing”, frontier.

- Peter H. Wiebe (2010), “Introduction to species diversity of marine zooplankton”, Science Direct.

- M. Sirajul Islam (2020), “Environmental reservoirs of Vibrio cholerae”, Science Direct.

- Michael J. Angilletta (2004), “Temperature, Growth Rate, and Body Size in Ectotherms: Fitting Pieces of a Life-History Puzzle”, Oxford Academic.

- (2022), “PLANKTON POWER — FIVE PLANKTON FACTS”, Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea.