Velvet Worm Profile

Studying ancient life forms is difficult at the best of times. Dinosaurs, for example, have left us around 700 to 1000 species in the fossil record so far, despite having roamed the Earth for around 200 million years.

And most of these are huge – relatively easy to find. So, finding fossils of tiny animals without skeletons from twice as long ago as the dinosaurs can be very exciting and very difficult.

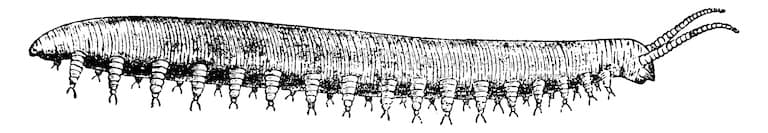

Luckily, some of the descendants of these ancient invertebrates still scuttle among us today, and give us some clues as to what early arthropods may have looked like. One such example is the velvet worm: a bizarre and ancient mystery that is still being peeled apart.

Velvet Worms Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Temperate and tropical, terrestrial, dark and wet habitats; leaf litter. |

| Location: | Asia, Africa, Central and South America |

| Lifespan: | Up to six years |

| Size: | 2.5 cm (1 in) to 22 cm (8.7 in) depending on species |

| Weight: | Not recorded |

| Colour: | Varied, generally blue-grey or brownish in colour, sometimes with patterns |

| Diet: | Opportunistic ambush predators of any small invertebrates |

| Predators: | Spiders, centipedes, rodents, birds |

| Top Speed: | Up to 4cm/s |

| No. of Species: | 243 described |

| Conservation Status: | Not Listed (IUCN) |

Velvet worms are very strange animals representing an entire phylum of around 200 known species.

They’re rare, even in places they belong, and we still don’t know all that much about them.

Thought to be related to arthropods, they lack an exoskeleton, have complex brains and give birth to live young.

Interesting Velvet Worm Facts

1. Mouth-first

The more we study the differences between organisms and try to categorise them, the more systematics and taxonomy become an infinite fractal of separations.

A phylum was once the largest grouping of animals you could find, but looking more closely, it seems that even above this level there are distinct differences in the biological makeup of the animals that fill it. We now group animals in many ways before they reach the phylum ranking, often based on development cues.

You’d be happy to hear that the first part of your body that was formed from the fresh new blastocyst growing inside your mother was your mouth. Unfortunately, it’s just not true. If you’re reading this, you started life as an anus.

You, and all the vertebrates, Echinoderms (starfish, brittle stars, urchins, etc), and even a phylum of weird, muscly worms called the Hemichordates, are grouped by the fact they originate from arseholes.

But not all animals do. Most arthropods, nematodes and molluscs begin life as a mouth, and velvet worms, traditionally grouped along with these, are still considered mouth-first, or “Protosome” organisms.

However, deeper research has now scrambled the simplicity of the mouth-anus divide, leading to deeper complexity within this taxon too.

It appears that velvet worms don’t subscribe to the butt-face dichotomy, and instead form a mouth–anus furrow that confuses everything. This isn’t the only thing that’s non-conformist about them, either. 1

2. They’re not worms

There’s very little agreement on what exactly a worm is, but we at least know what it isn’t, and velvet worms certainly fall into the isn’t category.

They’re thought to be related to arthropods and tardigrades, and the three phyla form a proposed taxon called Panarthropoda, though there’s less of a consensus about tardigrades.

Velvet worms may closely resemble the earliest forms of arthropod, and at least one fossil group dates back to around 300 million years ago, and the stem group is thought to date back 200 million years farther than that. While they share a lot of features with arthropods, their antennae, mandibles and feelers seem to have developed independently.

Some very clever molecular scientists are trying to tease out these links, but the trouble is, there are so few samples to extrapolate from. 2

3. There are only 243 species

200 species might sound like a lot, but at the phylum level, it’s almost nothing. The Arthropod phylum contains between 2 and 10 million species, depending on who you ask, and the phylum we belong to, the Chordates, has around 90,000. So, velvet worms have some catching up to do.

All the known species are grouped into just two families, and all are exclusively terrestrial, which is another odd thing for an entire phylum to be, but this might just be a product of the lack of data from the poor fossil record and the scarcity of live samples.

4. They have weird legs

What we do know is that these are not like other animals. Their locomotion is particularly odd: pairs of legs move together in synchrony when the animal is walking, and they’re tipped with little hooks which are used on hard terrain and moved aside to reveal soft, grippy cushions at their base when walking on soft ground.

The legs are moved by stretching and compressing the body itself, swinging pairs of legs with each contraction. Even the number of legs is unusual, with Australian species having between 14 and 18 pairs, and South American species having up to 43.

But perhaps the strangest thing about their legs is that in some species, females have more of them than males. This is true of the largest species, Mongeperipatus solorzanoi, from Costa Rica. 3

5. They have weird skin

Above these weird legs is a long, velvety body that the “worms” are named for. This is due to the lack of a hard exoskeleton, and a waterproof coating, coupled with a pressurised internal system that keeps them rigid.

This skin is shed every couple of weeks, and is still permeable to moisture loss from the inside, which is why these animals choose to stay in wet, humid leaf litter.

6. They’re photophobic

It’s probably this requirement for wetness that gives them their terror of bright light. Velvet worms don’t have eyes as we’d recognise one, but they do have a simple ocellus which can tell the difference between light and dark and this allows them to avoid drying out by energetically avoiding anything bright. 4

7. They’re smart

These weird animals have surprisingly complex brains, and this allows them to engage in some forms of social behaviour.

This is still quite an early branch of study on an organism that we don’t have a lot of data on already, so the extent of their behaviours is still unknown, but they do show dominance and submissive responses and a form of social hierarchy.

8. They spew slime

When hunting, and during self-defence, the Onychophora family of velvet worms uses a sticky slime that tangles up and captures prey or makes a potential predator all uncomfortable.

This goo sits in a special reservoir until it’s needed and is ejected forcefully at up to 5 m/s like the netted wrist ejaculations from Spiderman.

9. They give birth

Speaking of ejaculations, these animals almost all reproduce sexually, with one known exception.

This isn’t unusual at all for an invertebrate, but strangely, copulation can often occur before the female is of reproductive age, and she will just hold onto the sperm until she’s ready.

To make things even weirder, several species nourish eggs in a uterus by way of a placenta and then give birth to live young.

Velvet Worms Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Onychophora |

| Class: | Unknown |

| Order: | Unknown |

| Family: | 2 families |

Fact Sources & References

- Ralf Janssen (2015), “Fate and nature of the onychophoran mouth–anus furrow and its contribution to the blastopore”, National Library of Medicine.

- Russell J. Garwood, (2016), “Carboniferous Onychophora from Montceau‐les‐Mines, France, and onychophoran terrestrialization”, PubMed Central.

- Reptiliatus (2022), “GIANT RED VELVET WORM!”, YouTube.

- Katarina Samurovic (2022), “Are Velvet Worms Rare?”, Earth Life.