Mauve Stinger Profile

Cnidarians have been roaming the oceans for longer than it’s possible to truly imagine.

Not long after they show up in the fossil record, the class of true jellyfish follows: one that dominated the oceans during the Precambrian period, only to be toppled by the explosion of ocean diversity that came in to balance things out.

But the jellies haven’t forgotten what it was like when they were in charge, and thankfully, with a little help from a hyper-consuming ape species, the competition that evolved in the oceans over more than half a billion years is now all but wiped out.

And the jellyfish are ready to move in. The Mauve stinger is one species at the front of the charge, washing up on beaches and wiping out fish farms – a harbinger of worse to come.

Mauve Stinger Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Open ocean and coastal waters |

| Location: | Mediterranean, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans |

| Lifespan: | Estimated two to six months in the wild, 17 months in the lab |

| Size: | Up to around 12 cm (4.7 in) across |

| Weight: | Not listed |

| Colour: | Varied: from mauve, to pink, brown or yellow |

| Diet: | Zooplankton, small fish, crustaceans, other jellyfish, and eggs |

| Predators: | Turtles, bony fish |

| Top Speed: | Slow |

| No. of Species: | 1 |

| Conservation Status: | Not Listed |

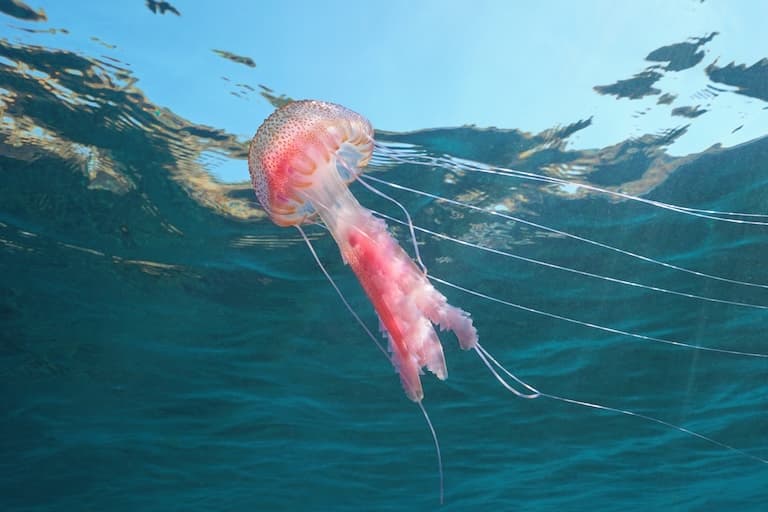

The Mauve stinger is a gorgeous species of jellyfish found mostly in the Atlantic and Mediterranean but with a very widespread presence that’s growing by the day.

Like the Nomura, making good headway in waters around Japan, this one has taken on responsibility for the Mediterranean territories, invading in huge blooms and upsetting tourists and fishermen alike.

These glow-in-the-dark Cnidarians are making a huge comeback as their competition is being decimated by the fishing industry, and not everyone is happy about it.

Unfortunately, the dip in profits and tourism income is the least of our worries – these ancient ocean rulers are a sign of much more worrying developments in our oceans.

Interesting Mauve Stinger Facts

1. They’re true jellies

The Cnidaria phylum is one of the more ancient alien phyla we see around us, yet it only contains around 11,000 known species today.

Once a dominant presence in the oceans, Cnidarians have been relegated to more of a supporting act to some of the more modern species that now feed on them.

They are found in both freshwater and marine habitats and make up lots of the radially symmetrical animals we find in the ocean, such as the anemones, hydroids, and jellyfish, the latter of which are members of the Scyphozoa class.

This class is exclusively marine and has existed since the beginning of the Cambrian period, containing some of the largest jellies around.

This is the class that is known as the “true jellies”, and within it, the mauve stinger sits in the Semaeostomeae, or “flag mouths” order, jellyfish which are characterised by four oral arms and square mouths.

2. They have an everything hole

This single hole leads to a single body cavity where all of the magic happens. Both ingestion and excretion occur using the same opening and pretty much everything else about this animal is ancient and simple, too.

Its nervous system is a basic net which covers the bell and aids in contractions for swimming, its digestion, gas exchange and fluid transport all occur in the absence of specialised organs like intestines, gills or a heart, and if this wasn’t clear enough already, the mouth is also the anus.

The only thing they can’t do with this hole is copulate, as this animal sexually reproduces in the boring external manner, by releasing its gametes into the water.

And this seems like they’re missing a trick because they even make glow-in-the-dark lube.

3. Luminous mucous

While simple, this isn’t a stupid animal by any means and has light sensing and odour pits across its bell.

This delicate animal is also very beautiful and comes in a range of colours, most obviously, the purple that gives it its name.

Not only are they beautiful in daylight, but they also glow in the dark. When disturbed, they release luminous mucous that is still the subject of study to figure out the chemicals involved. But these tender animals can also pack a punch.

4. They use salty stingers

The jellyfish nematocysts, or stinging cells, are a fascinating work of evolutionary engineering.

The stings of a jellyfish are essentially harpoons, blasted out using water pressure, and barbed to hold onto prey as the venom works to immobilise it.

To pull this off, the jelly tentacles build up a high concentration of ions behind the stinging cells, and when it’s time to fire, the walls of the tentacle become permeable to water.

Through the process of osmosis, water rushes into the region of high concentration of ions and expands the cells, inflating them like a balloon and forcing the stingers out.

This whole process happens remarkably quickly and is one of the fastest biological processes known. Some such stinging barbs can even pierce the shells of crabs, so human skin is no problem for them. 1 2

5. They grow up fast

These animals don’t live a long time, even under perfect conditions. In the lab, it’s around 17 months, and in the ocean, much less. Their delicate nature means they are easily damaged by rough waters, so they need to reproduce fast.

Within 230 days they are fully grown, and somewhere by three to four months, they are reproductive. Reproduction occurs by the spewing of gametes from the everything hole, and these are externally fertilised to skip the sessile polyp stage of many cnidarians and go straight to free-swimming larvae.

This is fast, but the real speed of their growth depends on prey abundance. Lately, this isn’t proving to be a problem for jellyfish in general. 3

6. They can cause problems

While they look like harmless Avatar balloon lights, these are true predators, and as such they can cause devastation to prey species when in large numbers.

Mauve stingers aren’t strong swimmers and are more or less at the mercy of the ocean, so when currents go a certain way, so do the jellies. This means they can form large clusters, all swept in together, and this can have a strong impact on prey in those areas.

But they also affect people. Tourists have been increasingly reporting stings from various species, this one included, especially in the Med’. This affects tourism, but they also clog up fishing nets and tear holes in them when brought up in fishing vessels, which impacts the fishing industry.

Stings from this species can be painful but aren’t thought to be life-threatening, what’s more of a concern is what these aggregations of jellyfish signal to us about the state of the oceans. 4 5

7. Jellyfish might be taking over the world (again)

In North Asia, anchovy caches are declining as Nomura jellies are blooming all over the place and eating all the little fish.

In the Western Mediterranean, the Mauve stinger is also blooming and making swimmers less inclined to go into the water.

But the focus of media attention on economic impacts on tourism and the fishing industry is about as insightful a take to this phenomenon as complaining that the firefighters are going to make your carpet wet when they put out your house fire.

Jellyfish blooms are on the rise all over the place, and it is a very bad sign. Economic incentives are destroying our global ecosystems in a staggering wave of sterilisation that will soon overtake even climate change as the most pressing issue of our time, and the jellyfish are a testament to this.

But to make matters worse, these two phenomena are intertwined, and while climate change makes extinction events worse, the reverse is also true.

The more we take from the ocean, the less stable our climate becomes. With more than 90% of large whale species now gone, the fish are following suit, and soon all that’s left will be plankton and the jellyfish that eat them.

By warming the climate and removing all the competition in the ocean, we have created the perfect conditions for jellyfish to bloom, and should they wipe out the zooplankton foundation for larger animals, this eradication event will only be accelerated.

The return of the Cnidarians may be already upon us.

Mauve Stinger Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Scyphozoa |

| Order: | Semaeostomeae |

| Family: | Pelagiidae |

| Genus: | Pelagia |

| Species: | noctiluca |

Fact Sources & References

- Gian Luigi Mariottini (2008), “The Mauve Stinger Pelagia noctiluca (Forsskål, 1775). Distribution, Ecology, Toxicity and Epidemiology of Stings.”, MDPI.

- Erin Leverenz “Pelagia noctiluca”, Animal Diversity Web.

- Martin K. S. Lilley (2014), “Culture and growth of the jellyfish Pelagia noctiluca in the laboratory”, Inter Research Science Published.

- “Massive Outbreak of Jellyfish Could Spell Trouble for Fisheries”, Yale Environment 360.

- Giacomo Milisenda (2018), “Seasonal variability of diet and trophic level of the gelatinous predator Pelagia noctiluca (Scyphozoa)”, PubMed Central.