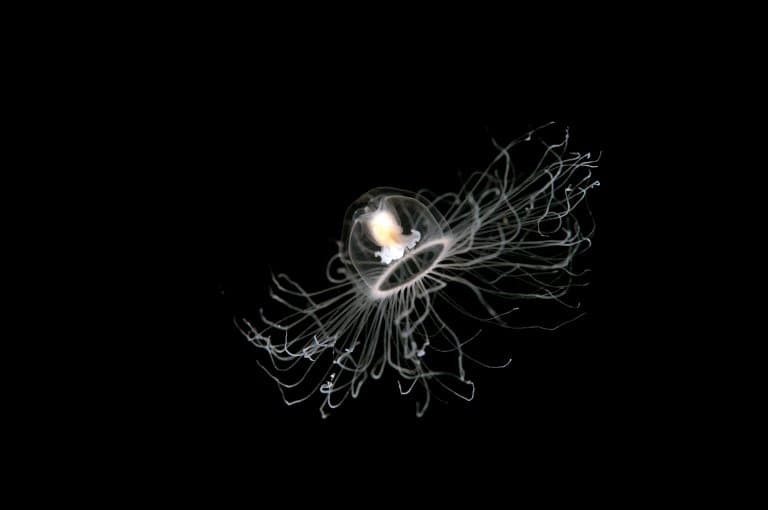

Immortal Jellyfish Profile

Most jellyfish live for around one to three years, putting in their time and then moving on.

They drift around, eating and reproducing, and then they die – leaving their matter to be recycled into the great nutrient bank of the ocean.

There’s one jelly that chooses not to do this. Instead, it regresses to an immature state and begins again.

This is the immortal jellyfish: an organism recognised in the fossil record since before the extinction of the dinosaurs. Could there be an individual alive today that witnessed this event?

Immortal Jellyfish Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Temperate to tropical waters |

| Location: | Worldwide |

| Lifespan: | Infinite |

| Size: | 4.5mm (0.2 inch) |

| Weight: | >1g |

| Color: | Transparent, with a red stomach |

| Diet: | Zooplankton |

| Predators: | Other jellyfish, larger fish and turtles |

| Top Speed: | Slow |

| No. of Species: | 1 |

| Conservation Status: | Not Listed |

Immortal jellies is a species of small jellyfish, that have a unique ability to reverse ageing.

They are inhabit temperate and tropic waters worldwide in all oceans, often in marinas or on the ocean floor. They are bell-shaped, and grow to around 4.5mm (0.2 inches) in height and width. Young immortal jellyfish have only 8 tentacles, whereas adults grow to have between 80-90 tentacles.

They are carnivorous and hunt using their tentacles as they drift in water. They sting their prey using nematocysts on their tentacles, although this isn’t dangerous to humans. They diet on zooplankton, fish eggs and mollusks.

We still don’t fully understand how they reverse their ageing, or what it means in the bigger ecological picture, but in studying them we learn a lot about our own fear of our mortality, of the role of death in ecosystems, and perhaps the potential dangers of allowing an animal with The Quickening into every known ocean.

Interesting Immortal Jellyfish Facts

1. They can relive their youth

What makes these animals so interesting to science is their ability to return to a juvenile state when stressed. While the behavioural equivalent is commonly seen in humans, as far as we know, these jellyfish are the only animals who can biologically achieve it.

Scientists discovered that when there is a certain level of environmental stress, such as a change in temperature or salinity, or physical stress, such as a big pair of researcher forceps snipping at its bell, the jellyfish will quickly regress to the state of a polyp.

A polyp, other than a medical inconsistency in your butt, is also the name given to the juvenile stage of certain ocean-going animals. These are the pre-sexual stages, unable to reproduce, and the stages that mature into the sexually-active medusae.

Polyps are little tubes with tentacles that sit on rocks without a care in the world, and it is to this state that the adult Turritopsis returns, seemingly as a way to isolate itself from difficult times. 1

2. Immortal does not mean invulnerable!

While this jellyfish does seem to hold the key to everlasting life, this trick is predicated on it avoiding being swallowed, crushed, or dehydrated.

It’s still more than capable of being killed, it just doesn’t seem to have a natural end to its existence.

Once it relives its childhood, it returns to its sexually-mature stage to have another go. This cycle has never actually been witnessed in the wild and happens too fast to catch in situ.

It’s presumed that it can be repeated indefinitely, but we still have quite a lot to figure out about why and how it works.

3. They can reprogram their cells

This is the meat of the issue. In most cases, tissues start as stem cells, without any programming, and these are quickly hardwired to reproduce as a certain type of cell.

This generally-irreversible process means that when cells are sent to your pancreas, they’re told to make pancreas cells, and when they’re sent to your hair follicles they’re told to reproduce as hair cells.

This way you don’t end up with a hairy pancreas or leaking insulin into your beanie.

This programming basically tells the cells which parts of the DNA to use to do their job, and they go ahead and do it. And they can’t change this. Once they’re specialised (or, differentiated), they’re stuck that way for good.

Except in the immortal jellyfish. This nifty little trick, called cell transdifferentiation, is exactly what it uses to return to its juvenile state, time and time again.

If we could figure out how to reprogram cells the way they do, we may solve the ageing and regeneration of tissues.

4. They excrete from their mouth

Turritopsis Dohrnii not only directs prey using it’s tentacles to it’s mouth and eats them, it also then excretes from the same orifice.

While this sounds quite gross, it’s all extremely efficient!

5. They are 95% water

Immortal jellies body composition is only 5% matter, the rest is water.

They are made up of 3 layers – An outer layer (known as the epidermis), a middle layer (called mesoglea; a jelly-like substance), and also an inner layer (gastrodermis).

This makes them quite popular for predators for snacks, so they are preyed upon by other jellyfish, sharks, sea turtles and penguins.

6. Death is a feature, not a bug

You might wonder why, if an organism can cheat death, does evolution clearly favour death as a strategy.

Dying is a necessary part of life for several reasons.

Without death, there’s less change and less diversity, and these are the very components of an ecosystem that make it resilient through extinction events and environmental shifts.

Death is also a protection against monopolies; a way to forcibly redistribute resources that have been hoarded over a lifetime.

It’s a key component to sexual reproduction, restricting an organism’s ability to propagate indefinitely and boosting the healthy competition that forms better organisms for their environment.

Cells are even programmed with a time limit to ensure that a new generation of healthier replacements can come up behind them.

We’re still discovering the numerous perks to death, but the more we study it, the more we realise that it isn’t simply an inevitable failing of life, but an optimal condition, programmed into organisms by evolution to improve their fitness and to propagate the best possible manifestation of life in the long run.

But, if this is the case, how does the immortal jellyfish fit into this philosophy? 2

7. They do die

It’s worth remembering that while these jellyfish can seemingly extend their lives indefinitely, the biological clock is only one cause of death. They’re still susceptible to predation, extreme weather fluctuations, or getting run over by a migrating tuna.

Death will still be very much a part of life, even for a biologically immortal organism.

The way that this life strategy fits into the bigger ecological picture will become clearer over time, but it’s safe to say that this life strategy doesn’t seem to be breaking any laws, yet.

8. They’re everywhere

One potentially ominous point to consider is that without ageing as a limiting factor, the onus is entirely on other organisms to keep the populations in check. And this happens without exception in a healthy and balanced ecosystem.

Unfortunately, with all the fishing going on, the ocean is no longer healthy and balanced, as most of the animals have been removed from it.

Climate change is also credited with a 5% decrease in biomass per degree of warming. Predatory fish alone have been reduced by two-thirds in the last hundred years.

It’s thought that increases in shipping have also contributed to the distribution of these jellyfish into areas they didn’t evolve to live in.

So, putting it all together, we’re left with a jellyfish that won’t die on its own, a reduction in predators of said jellyfish and a mass distribution of the jellyfish into new ocean territories where it now has plenty of ecological room to expand indefinitely.

So far, this doesn’t seem to have caused any harm, but if the Great Dying taught us anything, it’s that leaving a single organism unchecked in the oceans for long enough can destroy 90% of all life on the planet. 3 4

Immortal Jellyfish Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Anthoathecata |

| Family: | Oceaniidae |

| Genus: | Turritopsis |

| Species Name: | Turritopsis Dohrnii |

Fact Sources & References

- Ulrich Technau Robert, E Steele (2011), “Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: Cnidaria“, ResearchGate.

- “Programmed Cell Death (Apoptosis)“, National Library of Medicine.

- Emily Osterloff, “Immortal jellyfish: the secret to cheating death“, National History Museum.

- Chelsea Wald (2014), “Archaeageddon: how gas-belching microbes could have caused mass extinction“, Nature.com.