Gomphotheres Profile

Historically, palaeontologists recreate ancient animals quite wrongly. Early TV dinosaurs stood in hilarious, unrealistic positions with shrink-wrapped skin, and the thumb claw of the [Megatherium] was originally placed on its head before people realised what it was.

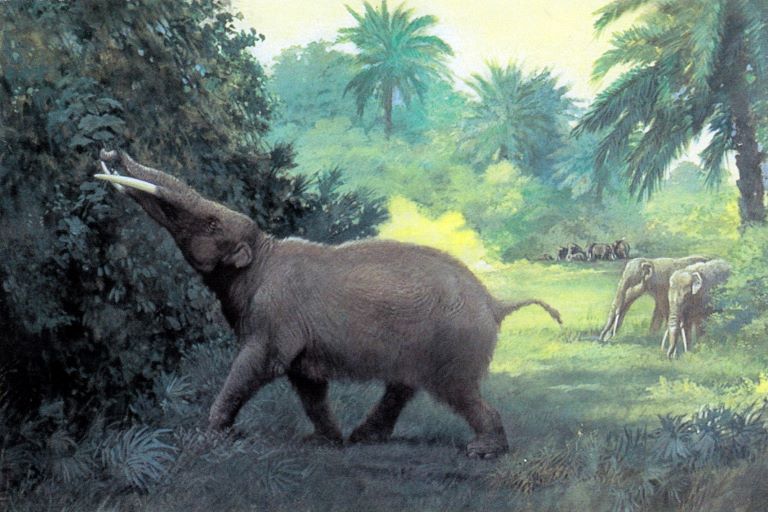

And when looking at Gomphotheres, you can’t help but wonder if they’ve got it wrong again. Or perhaps evolution, in its early attempts to produce an elephant, had to go through an embarrassing experimental phase to find its way.

Gomphotheres Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Grasslands, forests, marshes |

| Location: | Worldwide outside of Australia and Antarctica |

| Lifespan: | Unknown |

| Size: | From 1.8 to 2.5m tall (6ft to 8ft) |

| Weight: | Unkonwn |

| Colour: | Unknown |

| Diet: | Grazing and browsing: grasses, shrubs, roots and bark |

| Predators: | Large carnivores, humans, |

| Top Speed: | Unnown |

| No. of Species: | 20 known, likely many more |

| Conservation Status: | Extinct |

Gomphotheres are the perfect example of a Paleontological mystery. Their tusks are notoriously weird, but aside from that, there is so much detective work left to be done.

The shape of their trunks, the size of their ears, and even the purpose of their characteristic underbite is still up for grabs.

What we do know is that this is a lineage (or three) that was around for a seriously long time, and predated, perhaps even sired, the rise of mammoths and other elephants.

Yet, as Elephantidae took off, it was a long while before the Gomphotheres lost out to extinction.

Interesting Gomphotheres Facts

1. Tusks and Tushes

Gomphotheres are known for their very strange faces, but even this is not something common to all members of the family, and some animals previously classified as Gomphotheres have now been moved to their own family groups.

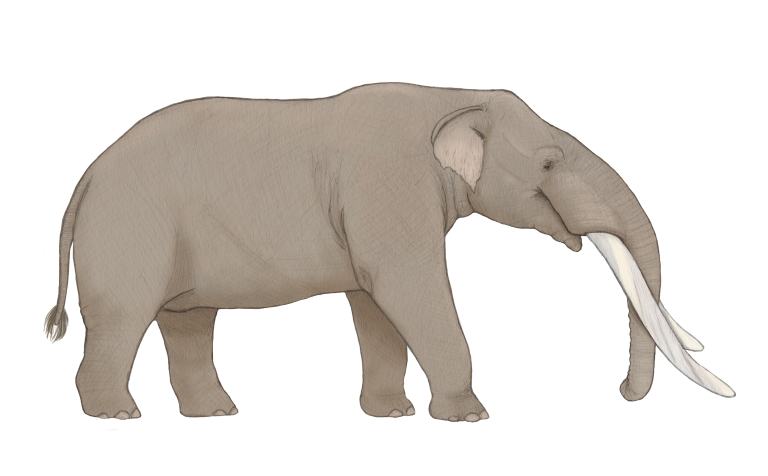

The major focus of Gomphothere classification is their tusks and tushes.

This sounds a lot like the advice given to pageant contestants, but in the context of elephant-like animals, tushes are a form of stunted tusk, as seen in female Asian elephants, and the study of their evolution gives us clues to the taxonomy of both extant and extinct proboscideans.

Some, particularly the most recent species, looked distinctly elephant-like. Others looked like failed experiments. Cuvieronius hyodon, for example, had both tusks and tushes, sprouting from the upper jaw. 1 2

2. They were very diverse

These facial arrangements came in various forms, and give insights into the lifestyle of the animals themselves.

Take Platybelodon, a genus of shovel-toothed Gomphotheres. These are starting to be considered part of their own family now, but their taxonomy isn’t entirely understood.

Regardless, there are some spectacular and terrifying depictions of this animal, with two upper tushes and a flattened pair of lower incisors that were thought to have been used for scooping up food like a forklift.

But newer research suggests they may have been used more like a saw than a shovel.

Whether this was used in swampy areas to dig up roots or to scrape bark from trees, is still a matter of debate. And since trunks don’t fossilise well, artists have had free reign to design the most freaky-looking depictions they could come up with.

And there were multiple different morphologies across the various species of gomphothere, the only thing they all really had in common was the extra tusks. 3

3. A second set of tusks?

Though these animals were mostly very strange-looking, their adaptations suggest a high amount of specialisation to their environment.

One of the defining characteristics of the group is the second set of tusks on the mandible. These tusks appear to have served various purposes depending on the species. Many were semi-aquatic, occupying niches similar to modern hippos.

Tusks in Gomphotheres were all over the place. Some species had tusks that curved upwards, some downwards, and others seemed to protrude straight out of the face. In at least one specimen, this extraordinary skull reached 2.7m long.

The skull of members of the Amebelodontidae family, for example, have such forward-facing tusks that they look more like a duck than an elephant. 4

4. And then we come to the trunks

As mentioned, the evidence on trunk morphology is lacking in the fossil record, but various species are thought to have had different-sized facial appendages. Some were more elephantine, others looked more like a Tapir’s snout.

Barytherium is often depicted with a short trunk, like that of an elephant seal, and were roughly two meters tall at the shoulder. The trunk is still a matter of argument, but being one of the earliest proboscideans in the fossil record, there’s not as much to go on yet.

Other species, like Stegomatodon, are portrayed as having a long trunk, but in some cases like this one, there is only one example of partial fossil remains to describe the entire species. So, as of yet, it’s likely our drawings of these strange beasts will become laughing stock in the face of technological advancements. 5

5. Conveyor teeth

But there are some things we can be fairly sure of. At the other end of the fossil spectrum are teeth. Not only do they last longer than pretty much anything else in the body, but they also hold significant amounts of information.

Despite being elephant ancestors, the teeth of the Gomphotheres were more mastodon-like. They had high protrusions, rather than ridged plates, suggesting a diet much higher in roughage and coarse material.

But unlike [mastodons], they would have teeth that continually fell out and were replaced, like elephants.

This dental adaptation may have been too specialised and could have been the reason the lineage went extinct, as the more effective grinding teeth of elephants and mammoths became advantageous in the Pleistocene when grasses became more abundant. 6

Still, they had an alarmingly good run.

6. They were very long-lasting

It’s debatable when exactly these bizarre proboscideans arrived on the scene but remains in Africa have been put forward as some of the earliest known, and if they’re accurate, this would place Gomphotheres at roughly 25-30 million years old.

They lasted so long that excavated early human settlements have gomphothere remains present, suggesting that they were part of human diets before their extinction around 12,000 years ago.

This lineage has unflatteringly referred to as “long-lasting ancestral stock”, but for good reason. It’s possible that Gomphotheres gave rise to the proboscideans we know best. 7

7. They may have been the original elephant

It’s unclear how the Gomphotheres relate to more recent mammoths and extant elephants, but evidence suggests they may have been an early ancestor.

Originating in Africa, it looks as though Gomphotheres greatly diversified and spread across most of the planet over the course of tens of millions of years, possibly giving rise to mammoths on the African continent, who then followed this migration and eventually outcompeted the older model.

Sadly, what were once the most widespread and diverse proboscideans on Earth, Gomphotheres are now remembered mostly in ridiculous artwork and obscure museum exhibits.

Gomphotheres Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | At least three families |

Fact Sources & References

- Dimila Mothé (2016), “The Dance of Tusks: Rediscovery of Lower Incisors in the Pan-American Proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon Revises Incisor Evolution in Elephantimorpha”, PubMed.

- JULIO LACERDA (2019), “Extinct elephant likely sawed, not shoveled with its mouth”, Earth Archives.

- RILEY BLACK (2011), “Another Use for Shovel Tusks”, National Geographic.

- W. David Lambert (1992), “The Feeding Habits of the Shovel-Tusked Gomphotheres: Evidence from Tusk Wear Patterns”, JSTOR.

- “Barytherium grave”, Prehistoric Fauna.

- Alejandro Hiram Marín-Leyva (2021), “The life story of a gomphothere from east-central Mexico: A multidisciplinary approach”, Science Direct.

- “Gomphothere Upper Molar (Shovel-tusked Elephant)”, Fossil Realm.