Giant Tube Worm Profile

Not long ago, classrooms around the world taught kids about the food chain, and the reliance that all living things, plants and animals, ultimately have on the sun.

The sun provides all of the energy for life, it was taught, regardless of if this energy is received directly – as it is with plants – or indirectly, as it is with the herbivores who feed on the plants, or the animals who eat those herbivores.

And so it was, we thought. That is, until we discovered the giant tube worm.

Giant Tube Worm Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Deep sea hydrothermal vents from 2,000 to 3,600m (1.2 to 2.2mi) |

| Location: | Worldwide, in volcanic regions |

| Lifespan: | Unknown, but some in the same family live for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years |

| Size: | Up to 3 meters (9 ft 10”) |

| Weight: | Unknown |

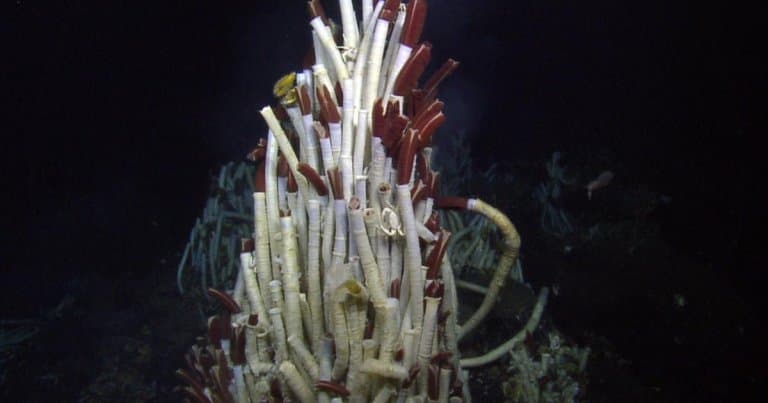

| Color: | Long white or grey tube with a bright red plume |

| Diet: | Sulphide water |

| Predators: | Crabs, possible molluscs |

| Top Speed: | Stationary |

| No. of Species: |

1 |

| Conservation Status: |

Not listed |

There are two animals commonly referred to as the giant tube worm. Since one isn’t really a worm, this article is going to be about the other; an annelid, much like your common garden earthworm.

Except this isn’t much like your common garden earthworm at all.

First of all, it’s enormous. Longer than you are, for sure. Secondly, it’s several kilometres under the sea. Third, it doesn’t eat or see, and finally, it has a shell.

Oh, and it lives on volcanic expulsions. Curious? Let’s take a closer look.

Giant Tube Worm Facts

1. They live in extreme conditions

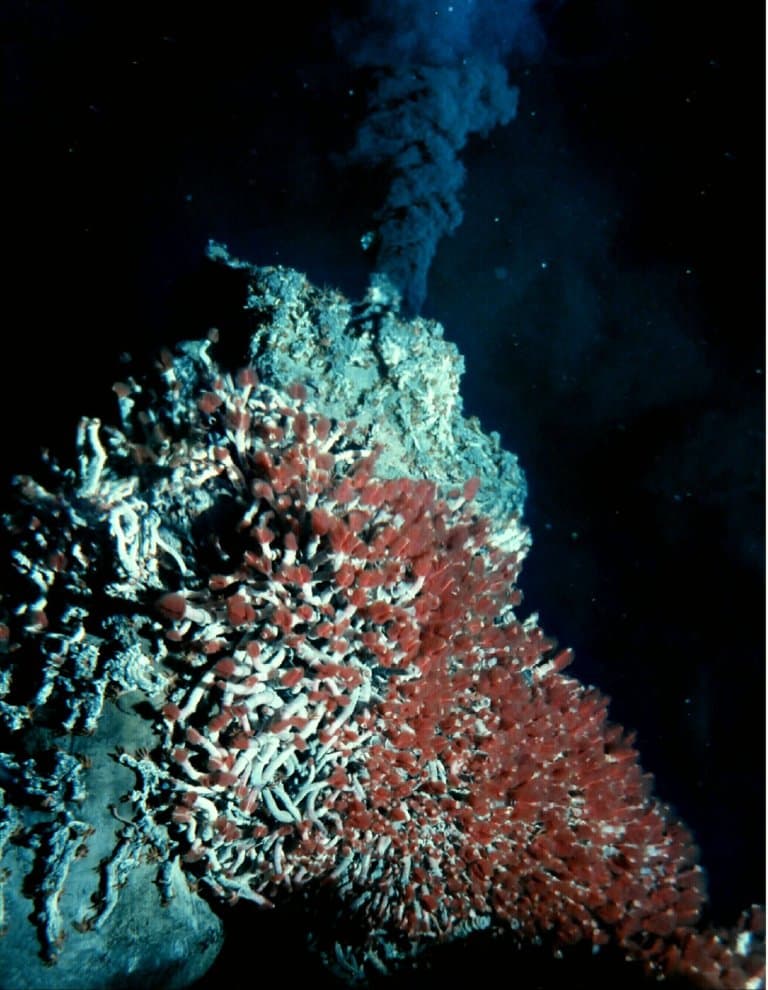

Not only do these worms live at the bottom of the deep blue sea – up to 3,600m (2.2mi) down – but they attach themselves to thermal vents, commonly belting out superheated water and gas at temperatures of up to 350–380 °C. Not only that, but they actually prefer vents with high amounts of particularly toxic hydrogen sulphide present.

While the vents do get exceptionally hot, giant tube worms choose a sweet spot between the frigid water of the deep and the boiling hydrothermal temperatures, choosing to sit at an impressive 54°C and below. 1

2. They don’t get their energy from the sun

These worms are unusual among organisms (though now we know they’re not unique), in that they have no requirement for sunlight at any point in their trophic (food) web.

They contain a particular kind of bacteria that thrives on the high sulphide content of the water spewing out of the vents, and this in turn provides every for the worm to live.

This means that the primary energy source for these worms is entirely chemical, and suggests new possibilities of life in unusual places. 2

3. They grow faster than any other marine invertebrate

Not only do they survive in these strange conditions and with these strange energy sources, but they also thrive.

They are extremely fast-growing, reaching lengths of up to 1.5m (4.9ft) in under two years.

This suggests that the pressure of the deep isn’t as much of a hindrance to growth rates as previously thought. 3

4. If the vent stops, they die

Nobody knows exactly how these worms colonise vents, but it’s likely they do so by sending out numerous larvae into the void.

These free-swimming immature versions of the worm settle where they may, and those on vents begin the process of colonizing them.

Changes in geological activity beneath the earth’s crust might eventually mean that the vent stops flowing, and in this case, the now fixed, mature colony will die off.

5. They don’t eat

Giant tube worms have no digestive system; instead, they’re just tall columns of absorbent worm mush that can take in toxic sulphide water that is then processed internally by their symbiotic bacteria. These bacteria make sugar out of the sulphide and produce waste in the form of sulphate.

The tube worm uses the sugar for growth and excretes the waste.

These microbes do so much processing of the sulphide water that they effectively remove it from the surrounding environment. In fact, calculations suggest that there must be another source than the vent itself, due to the insatiable appetite that a colony of tube worms must need to grow so large, so fast.

It’s hypothesised that there is a secondary source of sulphide that emanates from the surrounding mud, recycled from the sulphate waste of these worms.

6. Their colonies are enormous

If you’re ever lucky enough to visit a hydrothermal vent, you’ll likely be treated to the incredible sight of towering columns of these animals, as far as the eye can see and carpeting the sea floor in all directions.

The worms form a ring around the opening of the vent, stopping at an invisible boundary where the water temperature is intolerable. This space creates a scene of a vast alien gathering of worshipping arms, permanently reaching up towards the black smoke of the volcanic chimney.

Of course, if you aren’t ever invited to such a gathering, you’ll have to watch them online like the rest of us. Still, the sight is something to behold.

7. They have long, feathery plumes

While these animals don’t eat, they do have to breathe. They do so by sending out a long red plume of gill structures that reach out into oxygenated water.

This plume is rapidly retractable by a strong muscle at the opening of the tube, and will be quickly pulled out of harm’s way, should a nosy crab get too close.

8. They have a tube

It’s surprising that it took so long to mention this, really. But unlike almost every other annelid, this worm has a strong shelled tube made out of a carbohydrate called chitin.

This material is basically the animal equivalent of cellulose, which plants use for structure, and it’s common in insects and crustaceans, even in molluscs, but not so common in worms!

This tube is the mature worm’s home, and in the end, its prison; as it can never leave. 4

Giant Tube Worm Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Polychaeta |

| Family: | Siboglinidae |

| Genus: | Riftia |

| Species Name: |

Riftia Pachyptila |

Fact Sources & References

- Erin McLean (2017) “All Food Does NOT Come from the Sun“, Ocean Bites.

- “Activity for How Tube Worms Survive at Hydrothermal Vents“, BioInteractive.

- Lutz, R. A. (1994), “Rapid growth at deep-sea vents“, Sci Hub.

- “Vent Biology:Tubeworm Anatomy“, Dive & Discover.