Balloon Worm Profile

You’re probably not a passive detritivore who uses a mucous net to capture marine snow. You’ve probably never even considered it.

But the balloon worm is, and it’s living its best life. All it has to do is float about with its mouth open and all bases are covered. There’s one catch, though, and that’s regarding the true definition of “Marine snow”.

Balloon Worm Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Midwater marine |

| Location: | Pacific Ocean, Japan to Alaska, South America |

| Lifespan: | Unknown |

| Size: | 3.6 cm (1.5 in) |

| Weight: | Not listed |

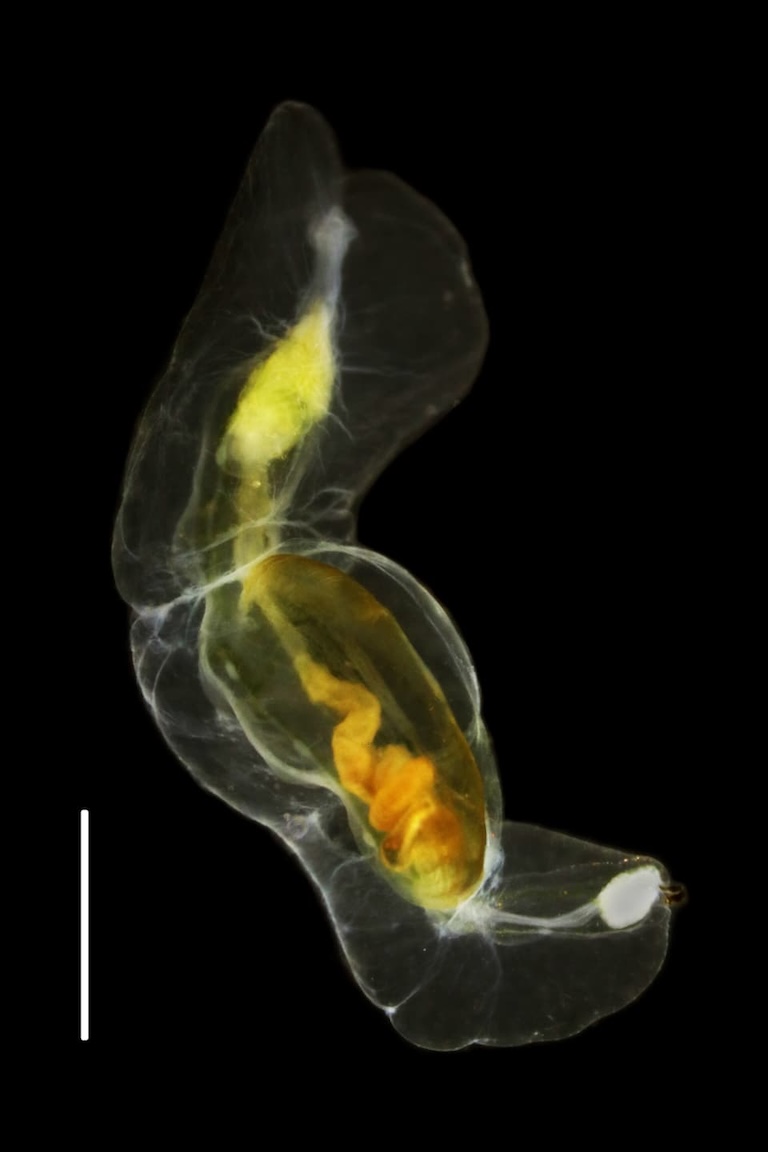

| Colour: | See-through, sometimes with orange or brown organs visible |

| Diet: | Marine snow |

| Predators: | Likely most things larger than it: fish, squid, Kakani Katija |

| Top Speed: | Planktonic |

| No. of Species: | 1 |

| Conservation Status: | Not listed |

Balloon worms are deep, darkwater cousins of the humble earthworm, even more closely related to tube worms, but unlike either of these relatives, they are neither properly segmented nor protected with a shell and instead float about, neutrally buoyant in the water column, extending a wide net of snot to catch falling detritus.

They can freak out when disturbed and do the characteristic wiggle of a worm panicking, but otherwise, they don’t move much at all.

Unfortunately, the trade-off for this is that they catch a lot of poo and get eaten by everything.

Interesting Balloon Worm Facts

1. They’re Annelids

Worm is a very vague term. It once meant anything that remotely wriggled, like snakes and beetle larvae; then it became a taxonomic class of invertebrates that grouped all sorts of wriggly things without backbones; but gradually it’s become more specific.

Still, now there are three phyla of worms, meaning that most of what we call worms still aren’t all that related to one another, but at least now they’re inclusive groups.

There are the flatworms and the nematodes, both of which contain some of the loveliest of parasites, and then the Annelids, which are the big juicy ones that get stuck in your teeth when you’re down in the garden as a kid.

There are parasitic Annelids, too, like leeches, but compared with the other two phyla, Annelida is relatively harmless.

The ones we know best are from digging in the garden: the earthworms. But this is an entire phylum of 22,000 known species of animals, and they’re found all over the place, including the ocean.

The best-known marine annelids are likely the polychaetes, named for having many hairs, and typically found in hard tubes protruding from rocks or hydrothermal vents.

The balloon worm is a member of this class of annelid but without the casing. And it’s a member of the bristle worms order, but strangely, it doesn’t look anything like these, either. 1

2. They’re not well segmented

Annelids are segmented worms, that’s the rule. Their bodies are ridged and separated into separate segments of more or less the same size, all the way down.

Many annelids, and polychaetes in particular, have hairs sticking out between these segments unappealingly, but balloon worms barely, if at all, follow these rules.

Their bodies are shaped like an inflated bag, with a distinct lack of obvious segmentation or bristles. On the outside it has a gel coating but, on the inside, the segmentation becomes more apparent. Nerve clusters are repeated down its length.

This bag-like shape allows it to float around in the water and it doesn’t really need to do much more than that. This is not a strong swimmer, preferring to stay put and catch food from above.

3. But they can wiggle

Along with clusters of nerves, the balloon worm also carries clusters of muscles, and when it’s disturbed, this balloon takes on a more familiar worm-like appearance.

Anyone unfortunate to have cut an earthworm in half with a shovel knows this wiggle, but it doesn’t require bifurcation to elicit the response from the balloon worm, as just brushing past it will send it into hysterics.

This is a great way to make a predator think you’re too insane to take on. But if that wasn’t enough, you could cast webs of mucous around you. 2 3

4. Mucous nets

Like several other floaty filter-feeders of the deep, the balloon worm hunts passively using a wide-cast net of mucous to gather as much of the nutritional content floating down from the brutal and chaotic world of the photic zone.

This net is sticky, and designed to hold onto any bits of detritus that descend upon it, after which the worm pulls it in and eats the lot.

5. They eat “Marine Snow”

This so-called “detritus” is also known as marine snow. That is, of course, if you’re feeling generous. If not, you can just call it poop.

Unless fish, turtles, or drunk honeymooning couples who couldn’t make it back to shore in time, have just had a particularly greasy kebab, when they crap in the ocean, their poop only goes in one direction, and that’s in the direction of the balloon worm.

Most of what they’re catching in this net is made of this poop. There will be other things, like the occasional scale from a mutilated fish, or various types of mucous, but of all the things that make up marine snow, poop is the most prevalent. So, that’s what this worm eats.

But most of the poop isn’t from whales or newlyweds, it’s from smaller animals like copepods and krill. And that’s because copepods are eating much of the whale and newlywed poop before it gets to that depth.

And if they aren’t, they’re eating the poop of the fish who did. The ocean is basically a vast conveyor belt of poop.

They also eat lots of tiny, single-celled dinoflagellates, but they’re probably full of poop too. 4

6. This is very important

Poop eating isn’t just great fun, it’s also really important. On land, it’s how faecal matter gets turned into plant food, but in the ocean, things are a bit different.

They’re also significantly more complex and less well understood, but in both ecosystems the role of the bottom-feeders or detritivores is significant.

The balloon worm’s diet suggests that they’re a big player in the remineralisation of particles as they sink from the surface. This process basically takes organic matter and turns it into inorganic matter that can then be used again at the lower levels of the food web.

7. They probably get eaten a lot, too.

It’s not clear what the predators of these worms are exactly, but being that they dangle there all sort of plump tasty looking, it’s likely they have quite a few.

Whether they have any chemical defences or can electrocute their enemies or shoot venomous barbs into their flesh is still all a matter of wild speculation one might use to jazz up an animal blog and not stemming from any scientific research. Yet.

Balloon Worm Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Polychaeta |

| Order: | Canalipalpata |

| Family: | Poeobiidae |

| Genus: | Poeobius |

| Species: | meseres |

Fact Sources & References

- Diane E. Robbins (1965), “The biology and morphology of the pelagic annelid Poeobius meseres Heath”, Zoological Society of London.

- MBARI (Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute) (2022), “Weird and Wonderful: The balloon worm floats in the ocean’s twilight zone”, YouTube.

- “All Animals Balloon worm”, MBARI.

- L. Uttal (1996), “Dietary study of the midwater polychaete Poeobius meseres in Monterey Bay, California”, Springer Link.