Giant Siphonophore Profile

Around 80% of the ocean remains to be mapped. A far greater percentage of the surface of the moon is well-logged in scientific literature, though to be fair, there’s a lot less to report from up there.

The ocean provides not only vastness but also depth, and this third dimension allows for quite a lot of weirdness to go unchecked.

In the layers of the ocean where sunlight doesn’t reach, animals live in ecosystems so different to ours that their evolutionary solutions become equally unfamiliar. And this is where things like the giant siphonophore – an animal longer than a whale and significantly squishier – thrive.

Giant Siphonophore Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Deep marine, between 700 and 1000 metres (2,300 and 3,300 ft) |

| Location: | Oceans worldwide |

| Lifespan: | Indefinite |

| Size: | Up to 50 m (160 ft) long |

| Weight: | Not listed |

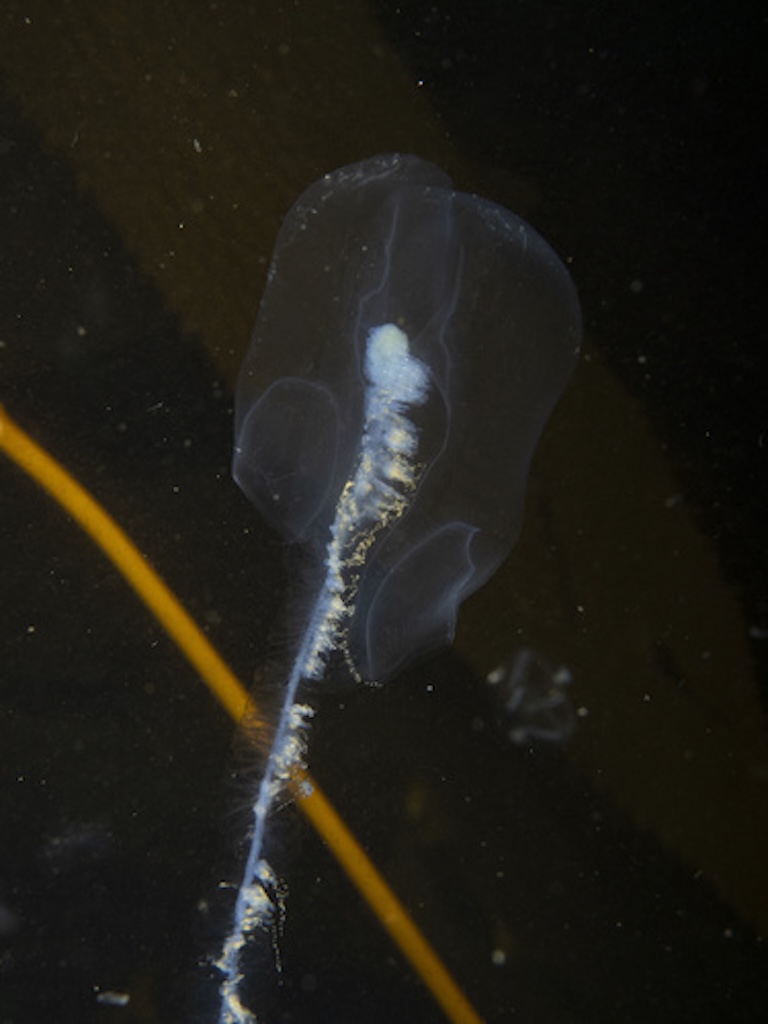

| Colour: | Transparent, bioluminescent |

| Diet: | Small invertebrates |

| Predators: | No known predators |

| Top Speed: | Slow moving |

| No. of Species: | 1 |

| Conservation Status: | Not Listed |

The giant siphonophore isn’t a single giant animal, but a colony of genetically identical and physically different little ones.

Like a marine ant colony, it patrols the oceans, each member serving a specific role to fulfil the greater need of the superorganism.

But the choreography is strong with these animals – working together they can swim as a single unit, cast nets, glow in the dark and kill… These are enormous, deep-sea predators, as delicate as they are lethal, and they might just live forever.

Interesting Giant Siphonophore Facts

1. They’re hydrozoans

Siphonophores belong to one of the oldest extant animal phyla on Earth: The Cnidarians. Cnidarians, whose phylum contains jellyfish, corals and sea anemones, are thought to be around 580 million years old, which would make them older than the arthropod, chordate and nematode phyla, to name a few.

By 540 million years ago, a class of Cnidarians called Hydrozoa shows up in the fossil record.

Many of these are small, solitary animals, but the class has a remarkable diversity in life cycles, growth forms, and physical form, including some incredible colonial forms such as the Man o’ War jellyfish, which is not a jellyfish at all, but a member of the Siphonophores: colonies of small Cnidarians pulling together to look and behave very much like one, despite being very distantly related.

Siphonophores push the boundaries of what defines an organism in ways that really highlight the weak spots in human categorisation systems.

Think of an ant colony, often referred to as a “superorganism”. This isn’t a single physical body, but a group of bodies working together to behave like a single organism. Colonial Hydrozoans are like this, but unlike ant colonies, they are physically connected to one another too.

Each individual is called a “Zooid”, and is entirely useless on its own – each needs the function of the entire group to survive.

The giant siphonophore, being up to fifty metres long, is often called one of the largest “animals” on the planet, but it’s not a single animal at all. Its current taxonomic position puts it into a family of around 20 related species, though within its genus, Praya, it is one of only two total species.

2. They’re long

Giant siphonophores aren’t all that massive – the blue whale is still the “Biggest” animal in terms of mass – but they do push up against the largest animal that’s ever lived in terms of length.

They do this by arranging in long stalks, with smaller zooids at one and larger ones at the other. The larger ones hold little gas sacs, which act as buoyancy aids, and the ones beneath them pulsate to create propulsion through the water.

This system works well to produce a colonial organism that can actively hunt smaller animals, and it does this in very dark regions of the ocean. 1

3. They’re mesopelagic

700 m (2,300 ft) to 1,000 m (3,300 ft)

If you’re interested in marine life, then a bit of terminology is worth the short time it takes to learn it, at least at the basic level.

The words “pelagic” and “benthic” do most of the heavy lifting, as they refer to the water column and the sea bed, respectively. Lobsters are benthic because they putter along on the ground; mackerel and tuna, who never touch down, are pelagic.

But the ocean is also very deep, so its ecosystems can be broken down into vertical zones. The photic zone is where the light from the sun reaches, and this is more or less determined by photosynthetic activity.

As far down as 200 metres, you’ll get photosynthetic organisms: algae and other such phytoplankton, that produce their energy from the sun.

Many of these organisms and the ones that eat them spend time in the photic zone while the sun is around and then descend to the relative safety of the layers below at night, into the aphotic zone, or the “dark ocean”.

Being much larger than the photic zone, this one is also broken down into layers. The first dark ocean layer is the mesopelagic, or, middle-pelagic: a thin band where around 1% of surface light reaches – not enough for photosynthesis.

This band is around 800 metres deep yet it contains perhaps the highest diversity of marine life, including animals dropping down into it from the photic zones, and those coming up from the zones beneath.

At 1km down, where the pressure really starts to get crazy, we see the alien creatures of the deep start to dominate over the more familiar, fish-shaped things we tend to eat. This is where the bathypelagic zone begins, and this one is huge.

Its isolation from the surface makes this a remarkably stable environment, sitting steady at around 4 °C and a salinity fluctuation of only 2 g/kg. And this has been stable for thousands of years.

Below this is the abyssal zone, which sounds scary enough, but even deeper still, in places like the Mariana Trench, there is the Hadal zone, named after the Greek god of the underworld. This is the deepest part of the ocean and ranges from 6,000 to 11,000 meters. This is deeper than Everest is tall.

Giant siphonophores have mostly been found in the mesopelagic zone, but this may be a sampling bias, as the bathypelagic beneath it is very hard to get to.

4. They glow in the dark

Down here there’s no visible light coming from the surface, but many animals can still see. In fact, there are animals beneath, in the bathypelagic zones, that have enormous eyes just for this purpose. Light down here comes from bioluminescence, and this is used in numerous ways.

It can be used to attract a mate, or attract prey; it can be used to blind a predator, or it can be used to attract a different predator to come and eat the predator that’s trying to eat you. Bioluminescence can even be used to camouflage an organism against the faint glow of other bioluminescent animals.

The giant siphonophore is a predator itself, and very few are bigger, so it uses bioluminescence as a lure to attract its prey.

Where food is plentiful it casts a net of tentacles with stinging cells and turns on its fishing lure. Anything attracted to the light gets paralysed by the stings and consumed.

This species is also known to glow when disturbed, as seen by a submersible team who accidentally brushed into one, triggering “the most brilliant bioluminescent displays recorded” that lasted 45 seconds after the initial impact. 2 3

5. They could live indefinitely

In shallower water species, siphonophores are eaten by turtles and large fish and contain lots of parasites that burrow into them and hide among the stinging cells. Not so much is known about the animals that bother the giant siphonophore, though.

The reproductive strategy for these animals means that individual zooids are cloned over and over, replacing those that are lost with genetically identical members of the team.

Using this method of continuous replacement, they don’t really “die” as such, unless they get eaten. And the giant siphonophore, living just above the common hunting grounds for animals like the giant squid, has no known predators. 4

6. They’re delicate

Being immortal doesn’t necessarily mean you’re invulnerable, and this is an organism that can very much die, especially if it’s pulled up to the surface.

Being mostly made of jelly and expandable gasses means it’s vulnerable to popping as the pressure reduces on the way up to the surface, and could no doubt struggle to recover should a submersible drive straight through it.

Giant Siphonophore Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Siphonophorae |

| Family: | Prayidae |

| Genus: | Praya |

| Species: | dubya |

Fact Sources & References

- EVNautilus (2016), “Up-Close With a Siphonophore, a Colonial Organism | Nautilus Live”, YouTube.

- Widder, E (1989), “Bioluminescence in the Monterey Submarine Canyon: image analysis of video recordings from a midwater submersible”, Sci Hub.

- BBC Earth (2021), “What Lurks in the Midnight Zone? | Blue Planet II”, YouTube.

- Lydia Smith (2024), “Siphonophores: The clonal colonies that can grow longer than a blue whale”, LiveScience.