Sea Urchin Profile

The infamous Daleks of Dr. Who remained a bit of a mystery for the early episodes of the show. These TV baddies were only known from their hard-shelled mechanical exoskeletons and their wavy appendages.

It wasn’t until the second doctor that we finally got a chance to see gloop being put into the shell and to understand that the controlling force of these machines is a gelatinous mutated blob that’s so alien it could only occur in fiction.

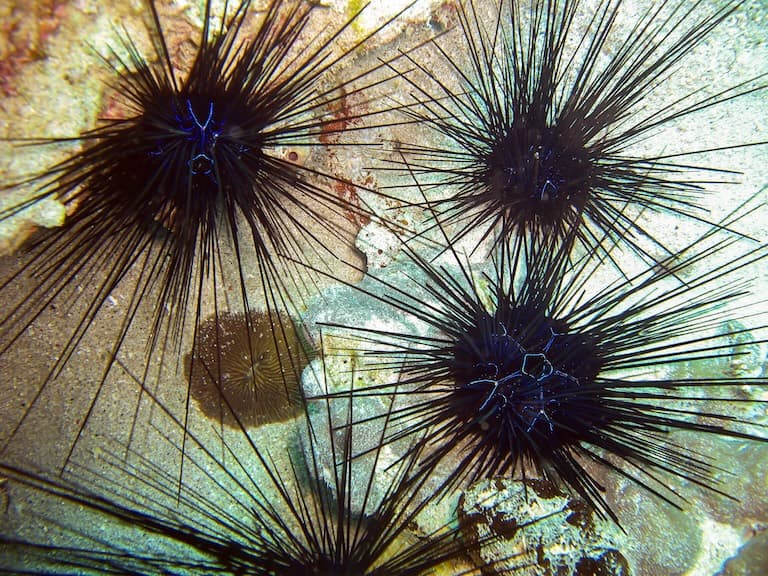

But in all the seas and oceans of all the world, there’s something very similar going on. Sea urchins, those hard, spiny balls that impale your feet at the beach, are in fact an ancient class of echinoderm, powered by a squishy – and some may say tasty – Dalek body.

Sea Urchin Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Marine, sea floor |

| Location: | Worldwide |

| Lifespan: | Possibly up to 200 years |

| Size: | From 3- 35cm (1 to 14 inches) across |

| Weight: | The largest can weigh up to 450g (1lb) |

| Colour: | Usually black or red, some pink, yellow, blue |

| Diet: | Mostly algae, some eat sea cucumbers and other animals |

| Predators: | Fish, starfish, crabs, marine mammals, humans |

| Top Speed: | Slow |

| No. of Species: | 950+ |

| Conservation Status: | From Least concern to Endangered (IUCN) |

Sea urchins are best known for the cool, round shells that wash up on the beach and the painful splinters they leave in your feet when you’re snorkeling carelessly.

And while they look like marine cactuses, they’re actually ancient and highly advanced animals that, while very slow, walk around on the sea floor like starfish, using special teeth and clawed spines to feed and defend themselves.

They are immensely diverse, and critical to coral health, yet, sadly, many are now in decline.

Interesting Sea Urchin Facts

1. They’re hugely diverse

Sea urchin life is far more diverse and widespread than we tend to give them credit for. Urchins are an entire class of animals, making up around a thousand known species and likely far more yet to be discovered.

There are two main subclasses, the smallest containing the most primitive versions of urchins, with thick and sparsely distributed spines, and the vast majority of species making up the larger subclass and containing at least 12 orders.

They’re found in every ocean in every climate, from the equator to the poles, and from the shallows to some of the deepest depths explored.

Their ancestor first appeared in the fossil record 450 million years ago, around the time life was taking its first tentative steps on land, and radiated into the range of species we still see today.

The smallest are 5.5mm across, and the largest a whopping 30cm in diameter. Some have tiny spines, others that are a foot long. And they come in all different colours! 1

2. They’re so Pentameric

Radially symmetrical organisms have a body type that converges to a central point (usually the mouth). Though weird on land, lots of animals in the ocean have this type of body, including starfish and jellyfish.

Radially symmetrical animals usually have 4, 5, 6, or 8 symmetrical body parts radiating in the same manner from the centre and urchins have 5.

This is known as pentamerism, and is why they’re so round. But they’re not born this way.

When urchins are fresh out of school, they’re bilaterally symmetrical. You might recognise this as what’s seen in all humans, insects, arachnids, fish, birds, turtles and pretty much everything else on land and much of the water.

But unlike all those examples, urchins morph as they mature into the spherical blob of spines they resemble as adults. They mouths are down on the floor and their buttholes are up at the top. And (thankfully) it was these mouths that Aristotle was fascinated with.

3. Aristotle loved them

Urchins feed by scraping algae off rocks and corals. This, as an ecosystem service, helps create premium real estate for the next generation of corals to colonise and so is really important to the health of the reef.

But they scrape the algae off using a strange set of teeth described by Aristotle as

“..continuous from one end to the other, but to outward appearance it is not so, but looks like a horn lantern with the panes of horn left out.”

He called it the Horn Lantern, and in tribute to the great thinker, we now call it “Aristotle’s lantern”.

This toothy apparatus is capable of digging into the substrate but sometimes functions too well, and the urchin gets stuck in its own hole. So, if you ever see one down a tube like this, please retrieve it or it’ll be stuck there forever.

4. They have an endoskeleton

The shell of an urchin is known as its test. This test is made of hardened calcium carbonate, converted from dissolved carbon dioxide in the water to form a rigid skeleton.

But while it appears to be on the outside, it’s actually covered in a layer of muscle and skin, which makes it technically an endoskeleton, as opposed to the exoskeleton we see in insects and crabs and such.

Still, most of the body is inside this shell, and the majority of what you can find on the outside are spines.

5. Their spines have jaws

These spines are bad enough on their own, but the smaller, closer ones even appear to have snapping little jaws attached to them.

These pedicellaria, as they’re known, are claw-shaped pincers found in a handful of oceanic animal lineages within the Echinodermata phylum.

They’re not very well understood and are found all over the urchin’s test, some even having evolved a venomous structure, suggesting that they’re a form of defence.

The flower urchin, a large, colourful species from the Pacific region, has four types of these pedicellaria, one of which is used to keep the body clean and another which opens like a flower but has a piercing barb that can penetrate human skin and can inject a medically significant venom into curious divers. 2

6. They can walk

Underneath all these spines, and surrounding the lantern-like mouth, are countless little flexible tube feet that are used to move the animal around.

These function very slowly, so at first glance, the urchins appear sedentary, but they do in fact roam almost constantly, and function a lot like snails, feeding on the leafy kelp forests.

On a good day, a particularly enthusiastic urchin might move up to 50 cm in a day. This is usually moderated by how much or little food there is nearby. 3

Sea Urchin Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Class: | Echinoidea |

| Order: | 13 orders |

| Family: | At least 8 families |

Fact Sources & References

- “Sea Urchins’ Teeth and Aristotle’s Lantern”, Living Coast.

- Simon E. Coppard (2010), “The evolution of pedicellariae in echinoids: an arms race against pests and parasites”, Acta Zoologica.

- Shazaad Kasmani (2018), “How Do Sea Urchins Walk”, YouTube.