Japanese Flying Squid Profile

We love to throw the word “flying” at anything that moves fast, especially if it does so off the ground, but the word does have a true meaning: it’s a form of controlled propulsion through the air that makes flying different than, say, gliding or falling.

Flying squirrels control their descent using a wide wing of skin called a patagium, but they can’t generate power – that’s all on gravity.

The same for flying lizards, flying fish, or any daring young man on the Flying Trapeze. But the Japanese common squid is exceptional.

This is a mollusc that doesn’t just jump and glide but has been shown capable of powered flight. As such, it’s been aptly nicknamed the Japanese flying squid.

Japanese Flying Squid Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Open ocean, coastal |

| Location: | Northern Pacific Ocean |

| Lifespan: | 1 year |

| Size: | Up to 50 cm (20 in) |

| Weight: | Up to 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) |

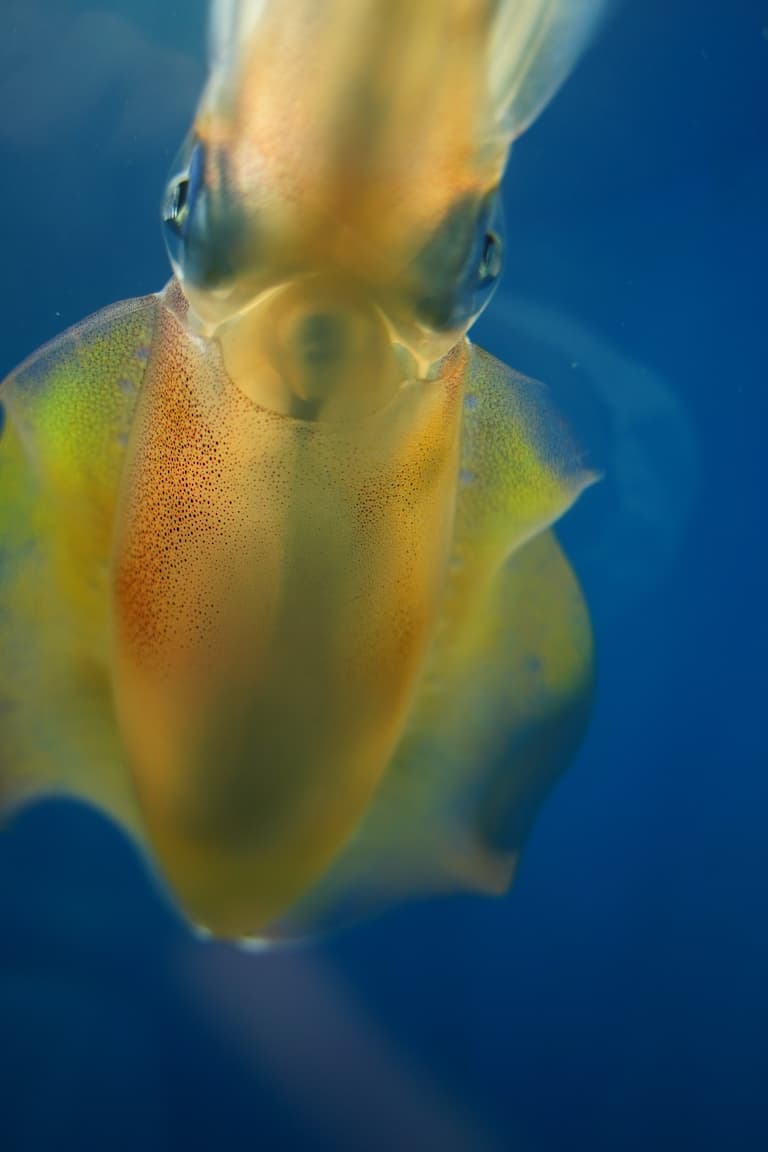

| Colour: | Grey/silver |

| Diet: | Uncertain, likely zooplankton and small fish |

| Predators: | Fish, birds, other squid |

| Top Speed: | 40 km/h (25 mph) |

| No. of Species: | 1 |

| Conservation Status: | Least Concern (IUCN) |

Japanese flying squid are members of one of the most infamous families of squids, known to be not only active predators but also powerful and intelligent animals ranging from very small to frighteningly big.

This species isn’t necessarily that smart, but it is fast, and it engages in epic migrations during which it uses a special jet-propelled jump to make things easier on itself.

But what makes this species outstanding is that it can further propel itself whilst in the air, crossing the line from gliding into powered flight, and becoming the first mollusc known to be capable of such a feat.

Interesting Japanese Flying Squid Facts

1. They’re Ommastrephids

These relatively small squids are members of a highly prestigious family of cephalopods known as the Ommastrephidae.

The name itself likely doesn’t ring a bell for most of us, but its members include the infamous Humboldt squid, known for its aggressive nature and frightening intelligence.

This is a family of active predators, characterised by two rows of sharp-toothed suckers on each arm, and an ability to generate a lot of power when swimming.

So, it’s not surprising that this species is capable of long-distance travel.

2. They migrate

This species of squid typically grows to around 30cm long, sometimes up as much as 50 cm all-in, but despite the size, it’s capable of joining its friends in the thousands to travel across migratory paths that will take them over 2,000 km from their starting point and back.

These migrations are all about feeding and mating, the latter of which occurs rather matter-of-factly as the sexually mature male politely hands an immature female his genetic package to keep for when she’s ready to use it (This is not a recommended strategy among humans, no matter how politely it’s offered and is very much only OK if you’re a squid).

What’s particularly important about this mating strategy is that since the packets of sperm aren’t directly deposited, they come with their own ejaculatory mechanism.

This is a sort of timed device set to go off at an appropriate moment and force the male’s wiggly little fellas into the female reproductive system.

Unfortunately, they aren’t able to distinguish between the soft fleshy tissue of a female squid and the soft fleshy tissue of a human mouth.

3. They might ejaculate in your mouth

At least one case of a flying squid misfire has been documented in the Journal of Parasitology, in which a 63-year-old Korean woman took a bite of undercooked squid and was met with a sharp stabbing pain.

She spat out the offending morsel but was followed by a persistent, wriggling, penetrating sensation, and once at the hospital, a series of twelve little worm-like masses were extracted from her oral cavity.

These were identified as squid sperm.

This is one reason, if you insist on eating them, to cook them first. But it’s not only their sperm that are highly energetic. 1

4. They’re rocket jumpers

When swimming, this entire family uses a powerful siphon that takes water in from one side and forces it out through a narrow hole to create jet propulsion.

The Japanese flying squid can accelerate so fast that they can propel themselves out of the water at alarming speeds.

It’s thought this allows them to reduce the energy costs of swimming, as the air produces far less drag, and it may have some predator-avoidance applications, too, though it’s more likely it doubles the danger by bringing the poor creature into bird territory.

Still, while this is considered jet propulsion in the water, it’s more accurately a rocket once it’s in the air. 2

5. But they can actually fly

It’s commonly said that flight has evolved independently four times: in birds, bats, insects and pterosaurs. Well, it appears that we can add molluscs to this list, albeit a rudimentary form of flight.

Still, rocket propulsion might be unique to squids, who appear to use it once they’ve left the water, and until the fuel (water) has expired, at which point they’ll crash back into the water to refuel.

What makes this different from the flying fish and other flying animals is that they are able to expel water while in the air, generating force, and navigating to some degree by manipulating their fins and arms.

They can cover distances of over 30 m using this strategy and reach speeds of up to 40 km/h. Sadly, this fast pace isn’t something they can keep up for long. 3

6. Live fast, die young

In classic cephalopod fashion, these little squids are somehow programmed to pop their clogs immediately after popping their genetic loads.

Their lifecycle is experienced at a high rate, hatching in their spawning sites, maturing quickly, migrating, feeding, mating and then dying all within a single year.

Females will release anything from 21,000 to 200,000 eggs in a large jellied sausage of up to 27 cm long. Then, they too will die. Unfortunately, despite being so common, they’re hard to study out of the ocean. 4

7. They don’t do well in the lab

Lots of cephalopods do badly in shallow water because they’re so used to the deep ocean, but this isn’t the issue with the flying squid. Instead, this species appears to become stressed when isolated from its kin, suggesting there’s some critical social element to their health.

Having said that, they’re more than happy to eat one another when in close quarters.

As it is, they’re still remarkably common squid and make up a huge amount of the cephalopod biomass consumed in the countries surrounding their habitats.

So far, they’re listed as of Least Concern by the IUCN but as with almost everything, their numbers are dropping and their populations are being harvested unsustainably, so this will be subject to change. 5

Japanese Flying Squid Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Oegopsida |

| Family: | Ommastrephidae |

| Genus: | Todarodes |

| Species: | Pacificus |

Fact Sources & References

- Gab-Man Park (2012), “Penetration of the oral mucosa by parasite-like sperm bags of squid: a case report in a Korean woman”, NIH National Library of Medicine.

- Ron O’Dor (2012), “Squid rocket science: How squid launch into air”, Science Direct.

- Harumi Ozawa (2013), “Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s a squid”, Physorg.

- “Todarodes pacificus”, IUCN Red List.

- Deep Marine Scenes (2022), “Facts: The Japanese Flying Squid”, Youtube.