Woodpecker Profile

Woodpeckers make up at least 240 species of bird, separated from the passerines, or songbirds, before singing was fully invented.

But they found their own way to communicate, and while the songbirds were forming intricate choirs to welcome in the day, these alternative birds took a more bassy and percussive approach, banging their heads to a different genre entirely.

Woodpecker Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Most in tropical forest, but also woodlands, savannahs, scrublands, bamboo forests, grasslands and deserts |

| Location: | Everywhere except Australasia, Madagascar, and Antarctica. |

| Lifespan: | 4 – 11 years depending on the species |

| Size: | From 7.5 cm (3.0 in) to 53 cm (21 in) |

| Weight: | From 8.9 g (0.31 oz) to 516 g (18.2 oz) |

| Colour: | Highly varied |

| Diet: | Most are insectivores but opportunistic omnivores |

| Predators: | Mustelids, raptors, cats |

| Top Speed: | Unknown |

| No. of Species: | 240+ |

| Conservation Status: | Least Concern to Critically Endangered (IUCN) |

As any real rocker will know, headbanging for prolonged periods can take a toll on your body. It’s hard on the neck, it’s hard on the liver, and that’s only if you’re doing it in the air.

If you’re banging against a tree trunk, it can be even more uncomfortable but the woodpeckers have evolved to be the best at it.

These birds are master drummers and distribute forces so well they can keep a casual 2,280bpm with one beak without giving themselves a headache. Nobody wants to mess with that!

Interesting Woodpecker Facts

1. Their systematics are all over the place

Some people will say that systematics and taxonomy are totally different things, and they’re technically right, but it’s really only taxonomists who complain about it.

Systematists were, apparently, making unreasonable assumptions about woodpecker feathers that led to five subspecies being categorised by taxonomists, who then decided that wasn’t enough to go on and decided there should be only 3.

These three are (currently) the subfamilies Jynginae, commonly called wrynecks; Picumninae, the piculets, and Picinae, the true woodpeckers.

Wrynecks are small, old-world woodpeckers. They’re sometimes called snake birds, on account of their Exorcist-like defence mechanism that involves rotating their heads 180 degrees and hissing loudly. Terrifying.

Piculets are mostly South American woodpeckers, and they spend more time perched on branches than the other two, on account of a lack of supporting feathers in the tail that helps them not fall off trees.

Then, the true woodpeckers are found all over the place outside of Madagascar, Australia and Antarctica.

All have weird feet, and all make a lot of noise by banging their faces into tree trunks.

2. They’re drummers

Woodpeckers do peck wood, but just how much wood a woodpecker pecks is determined by what it’s trying to accomplish.

Drumming, as it’s called, is used to attract mates, but it’s also a way to define territories. Their ‘hoods are defined by a perimeter of their favourite drumming trees, which they visit frequently to bang on, carving out a clear boundary to their competitors.

They also peck to extract food, to stay in touch with their lovers, and to generally replace the passerine song.

Woodpeckers are so good at drumming, and its intricacies are entirely lost on us. The Japanese pygmy woodpecker is the fastest known, able to strike its drum around 38 times in a second. Far from being a basic and brutish behaviour, the woodpecker sound is diverse and intricate and distracts people from its strange toes. 1 2

3. They have weird feet

Woodpeckers have zygodactyl feet configurations. This is the nerdy way of saying their middle two toes point forward and their outer two point backwards.

Perching birds prefer three digits at the front with an opposable hook at the back, but for woodpeckers, this would get in the way of their woodpecking, so they’ve evolved a more balanced arrangement for sitting vertically on a tree trunk.

They’re so good for this purpose that the birds can walk straight up a trunk. Their legs are also short and strong for this purpose.

4. And incredible beaks

As you might expect, the beak of a woodpecker is a specialised organ. Of the three subspecies, the true woodpeckers’ have the best beaks, and the tips of these are self-sharpening chisels formed of hardened layers of keratin, supported by an internal bone structure.

But inside the beaks is an even more incredible organ.

5. They could lick their eyebrows

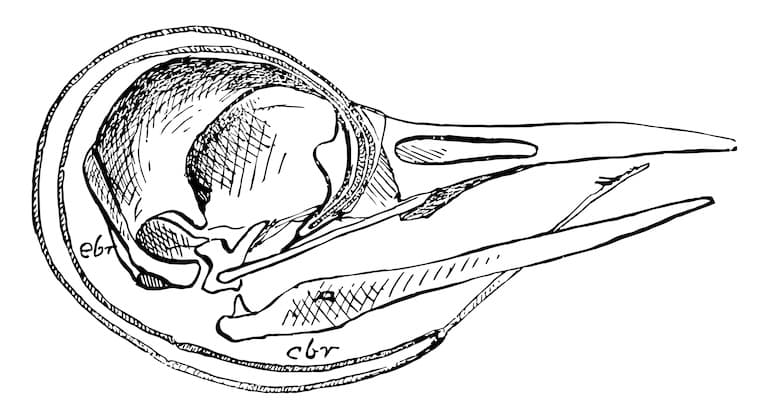

Human tongues are the only muscle that isn’t connected to a bone at both ends. But human tongues don’t even wrap around the skull.

Woodpeckers’ tongues do, though! Their tongue bone feeds through the skull and the tongue itself is tipped with a sticky barb, and is sent into cracks and crevices to wrap around the insect larvae found within. A combination of sticky saliva and hooks secures it in place and then the tongue pulls it back into to bird’s mouth.

This tongue is plenty long enough to lick their own eyebrows, though they apparently have the decency not to. 3

6. They have special heads

All of this goes on inside an incredible head that allows the average woodpecker to bang its face on a tree 122,000 times a day.

One great way to avoid a concussion is by having a small and smooth brain. Or perhaps that’s one result of it? Either way, this is the woodpecker brain, and it’s surrounded by a very thin layer of fluid to help hold it in place and help spread out the contact area between the brain and skull when drumming.

The skull itself is of course strong but made of a more compressible type of bone that’s like the padding in a motorcycle helmet.

Combined with the support of the hyoid bone attached to its tongue, these systems channel the percussive energy through the bird’s body, sending more than 96% of it away from the brain.

But this distribution of energy causes the skull to heat up, which results in the need for regular breaks to shed heat. Strong membranes over the eyes keep their retinas from falling off, and feathers protect their nostrils from filling with sawdust.

All this allows the woodpecker to slam headfirst into a tree at 1000 g. 4

7. Their pecking helps trees

You’d think all this drumming holes into trees would be bad for them but it’s generally a net gain. Woodpeckers pick more hollow, drier wood that resonates better, which means the damage they routinely do tends to cut down dead or dying branches, essentially performing amputations on the plant.

But they also work as fantastic pest control, feeding on boring pests that could cause a lot of damage if left unchecked. Taking ash trees as an example, one study discovered woodpeckers can remove up to 85% of these boring parasites from the host tree.

8. They need trees

But woodpeckers no doubt rely on trees, which are plants in decline all over the world. Most species are doing relatively okay but rampant deforestation threatens all species, and the Okinowa woodpecker is now critically endangered as a result of local tree decline.

Woodpeckers Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

Fact Sources & References

- Jim McCormac (2022), “Nature: The drum of the hairy woodpecker outpaces any rock ‘n’ roll star”, The Columbus Dispatch.

- Eric Schuppe (2021), “Evolutionary and Biomechanical Basis of Drumming Behavior in Woodpeckers”, frontiers.

- Pascal Villard (2004), “How do Woodpeckers Extract Grubs With Their Tongues? A Study of The Guadeloupe Woodpecker (Melanerpes Herminieri) in The French West Indies”, Oxford Academic.

- (2014), “Woodpeckers may be the answer to ash borer invasion”, uic today.