Quagga Profile

At the risk of beating a dead horse, it’s important to reiterate that the ecosystems that we rely upon for our very survival are rapidly decreasing in both biomass and biodiversity, and the scientific consensus is that a sixth mass extinction event is well underway.

And this is no accident of nature: humans are responsible. As we clear habitats for livestock, we kill off the previous tenants at an unsustainable rate, and in the instance of the quagga, a dead horse is a perfect example of this continued threat to our planet.

Quagga Facts Overview

| Habitat: | Plains and grasslands |

| Location: | Southern Africa |

| Lifespan: | Possibly 40 years |

| Size: | 2.6m (8’ 5”) long, 1.3m (4’ 5’) tall |

| Weight: | Up to 300kg |

| Colour: | Striped head, fading to a rusty brown half way |

| Diet: | Grasses and forbs |

| Predators: | Humans, lions, leopards, cheetahs, wild dogs |

| Top Speed: | Unknown |

| No. of Species: | 1 |

| Conservation Status: | Extinct |

The Quagga was a quirky subspecies of zebra from South Africa, once numbering in the tens of thousands, and rapidly hunted to extinction to make way for livestock grazing in the 1800s.

They had a few characteristics that were unique from their stripy kin, and while we’re still rampaging through the last of the wild habitats in Africa, there are some who are trying to reverse the process and use the very closely-related Plains zebra as a starting point for back-breeding Quaggas into existence again.

Interesting Quagga Facts

1. Just another horse tiger

There were once several genera of horse-like animals roaming around within the Equidae family, all different shapes, colours and sizes. All but one have now gone extinct.

All horse-like animals we have around today are part of the same genus, Equus. Despite donkeys (or, asses) being significantly smarter, better-looking, less phobic of everything, and all-round better than horses, they’re only very slightly different; and zebras, too, share the vast majority of their DNA with the other six species in the genus.

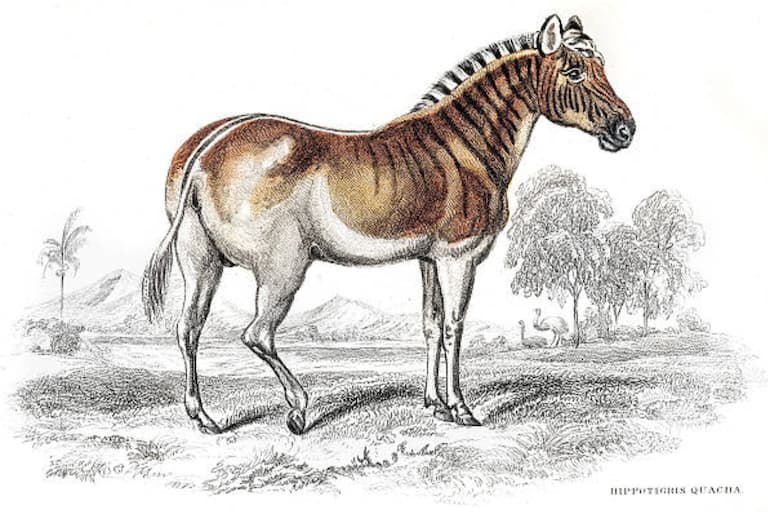

But this is where it gets a bit weird, taxonomically. There are three extant species of zebra, differentiated from other Equids under the subgenus Hippotigris (which translates roughly to horse tiger).

From genetic evaluations, it’s thought the Quagga is likely to have been a subspecies of one of them, the Plains zebra, Equus Quagga. 1

2. They once formed vast herds

This subspecies got a lot done, though. They were once prevalent in the Southernmost region of Africa, in what is now South Africa, as far North as the Orange River.

This landmark may have represented one of the physical barriers that separated this subspecies from its Plains zebra ancestors, tens, maybe hundreds of thousands of years ago during the Pleistocene, and led to it becoming a distinct subspecies in the first place.

Regardless, they were likely one of the dominant herbivores in the region and were said to have formed enormous herds on the grassy plains. 2

3. They were different

In Quaggas, females were both taller and longer than males. This is not unique in mammals, but it is unusual, and even more noteworthy is that it’s unique among all other known species of zebra.

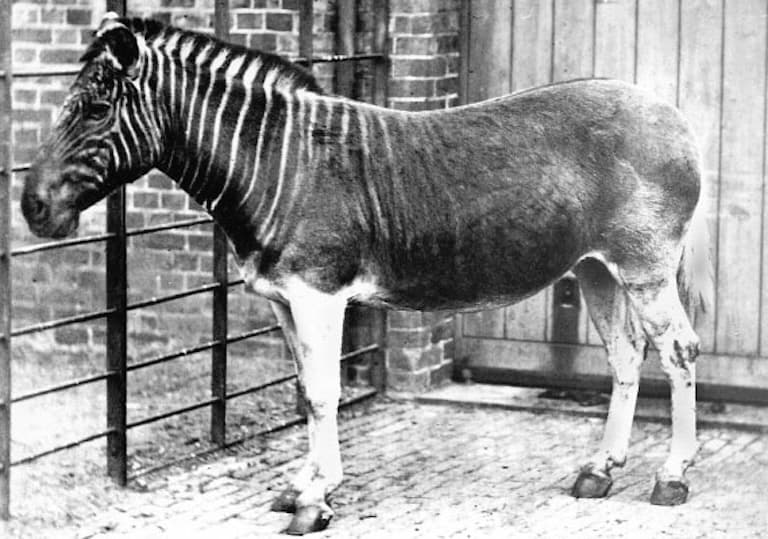

Quaggas also had a unique coat pattern, much like a backwards okapi, with the classic zebra stripes beginning at the head and fading into standard uniform reddish-brown colour somewhere around halfway.

But more than this, there was a significant variation between individuals, something which confused early taxonomists who were trying to classify species and subspecies simply by looking at them. 3

4. By 1872 they were extinct in the wild

Quagga hunting exploded in the 1800s, as colonists shot them in huge numbers for their hide and meat, as well as for sport.

They were also persecuted as competition for the vegetation that settlers wanted to protect for their livestock, so in South Africa, the subspecies didn’t stand a chance.

While the meat was said to be good – at least good enough for labourers – and the skin was commonly used to make leather bags, the majority of the Quagga’s population loss was down to deliberate extermination drives by colonists and a rapid uptick in hunting in the area.

Hunting grew as a sport, and the region became known as a “hunter’s paradise”, which is also something which has led to the demise of numerous species across the continent.

Had there been any sense of conservation for the animal, it would have been anyway nullified by the fact that it was not recognised as a different animal from the plains zebra, though this attitude wasn’t prevalent.

The last photo of a Quagga dates to somewhere between 1863 and 1870, shortly after which the last wild animal was killed. The last living quagga died in 1883, in Amsterdam Zoo. 4

5. They were the first extinct species to have their DNA studied

Quaggas went extinct so recently that there’s ample DNA available to study, and since the topic of DNA only came about with its discovery in 1869, this period represented the early days of DNA examination.

Most of this was done on animals that actually existed, of course, but by 1987, the concept of de-extinction was gaining traction and the Quagga became the first extinct subject for examination by naturalists hoping to bring back the extinct zebra. 5

6. They may be making a comeback

On account of how genetically similar the Quagga was to the Plains zebra, some scientists believe it’s possible to selectively breed the latter in a way that basically reactivates the Quagga genetics, essentially de-extincting the subspecies.

The Quagga Project has begun work on this already and claims to host three viable herds of “Rau Quaggas”, named to differentiate between the extinct quagga and refer to the project zebras being used as breeding stock.

They’ve already witnessed a change in their appearance and an increase in diversity among the herds, suggesting there’s something in the environment that caused quagga populations to present with this polymorphism. 6

7. This is a very rough science

Selective breeding typically works using morphological metrics. This means that individuals are selected for their visible traits, and in accordance with traits of the target species that are known to science.

But for extinct animals, there are so many genetic variables that aren’t visible, such as unique adaptations to habitats, or other behavioural attributes unique to the animal that can’t be deliberately selected for.

This makes the practice of back-breeding quite crude as a way to revive a species or even a subspecies like the Quagga.

It may be that the result of such programs is simply a plains zebra with a quagga coating, or it may be that with more research and investment, it becomes possible to identify and select for more precise metrics of the target animal.

So far, it remains to be seen how effective this process can get.

Quagga Fact-File Summary

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | quagga quagga |

Fact Sources & References

- Jennifer A Leonard (2005), “A rapid loss of stripes: the evolutionary history of the extinct quagga”, The Royal Society.

- “quagga”, Britannica.

- Peter Heywood (2020), “Sexual dimorphism of body size in taxidermy specimens of Equus quagga quagga Boddaert (Equidae)”, Taylor & Francis Online.

- Sarah Zielinski (2011), “Quagga: The Lost Zebra”, Smithsonian Magazine.

- Ross Kettles (2023), “The quagga’s extinction and revival: Fact or fiction?”, Nuwejaars Wetlands.

- Reinhold Rau, “The Quagga Project explained”, Universiteit Stellenbosch University.